The artist’s work is featured in a major retrospective at Walker Art Center in Minneapolis until Sept. 3.

If you’ve ever visited Batanes, there’s a chance you’ve touched down at Fundacion Pacita, a fantastic, colorful mountainside residence overlooking Boulder Beach that was Pacita Abad’s art studio late in her life, when she had stopped her itinerant ways. “Pacita built it when she knew she was diagnosed with cancer,” says her nephew Pio Abad, an artist now residing in London. ”And she really wanted to spend her last years in Batanes painting in the studio, in a place on the edge of a cliff overlooking the Pacific.”

It’s a great location, with its mosaic-tiled lodges and stone-pebbled residence, and stone sculptures gazing out at visitors. ”There’s this incredible calmness about it,” says Pio, “but underneath that calmness, Batanes weather can be very temperamental. So there’s this sense of calm and turbulence, you know, bubbling under the surface.”

It could describe his aunt. Pacita Abad wasn’t really meant to be an artist. Born in Basco, Batanes but educated at UP Diliman in the thick of the first Marcos years, the fourth of 12 children in a politically active family was meant to study law and enter politics. “Interestingly it was Pacita who was supposed to be the politician,” Pio recalls. “My dad always said she had the temperament for it.”

In the late ’60s, she was involved in the First Quarter Storm. But art found her instead, and she became a gypsy of sorts, traveling to over 60 countries in her life.

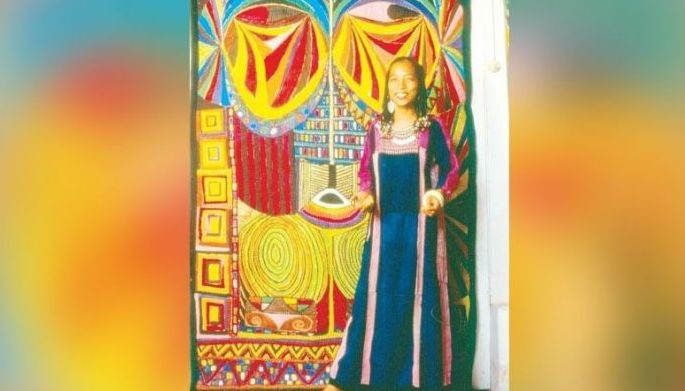

That artistic journey is now captured in a major retrospective at Walker Art Center in Minneapolis, Minnesota. Launched last April 15, “Pacita Abad” runs until Sept. 3 before moving onto San Francisco MoMA, and it’s the most comprehensive view yet of Abad’s prodigious output — some 5,000 artworks sourced worldwide, whittled down to 100 key pieces. The themed rooms include her unique trapunto textile pieces, interwoven with shells, beads, buttons, mirrors and other found objects; Social Realism pieces that reflect her political consciousness; a room focused on the Immigration Experience; and Masks from Six Continents, reflecting her deep immersion in global culture, often flipping the colonial order on its head. It’s not only the biggest exhibition ever mounted for a Filipino artist in America, but one of the largest exhibitions currently showing in the US.

In the exhibit there’s a photo of young Pacita, student activist, meeting face to face with then President Marcos in Malacañang. A few months after that, an associate of Marcos would machine-gun the Abad family home from end to end. (Pio’s parents were also political targets under the Marcoses, a theme he’s come back to often in his own work.)

No one was hurt in the attack, but Pacita — the center of political attention — decided it was time to leave. She continued her studies in America, the beginning of her journeys abroad.

Though she studied at Corcoran School of Art in New York in the ‘70s, she was largely self-taught, drawing from traditional and folk art and everything else available wherever she traveled, usually with husband Jack Garrity, who worked for World Bank. Developing a personal visual style, Pacita’s work reflected her intellectual, artistic and political development through a unique vocabulary of images and icons, blending fine art and craft, as though the categories no longer mattered.

Yet Pio thinks she’s never really been given her proper due as an artist, even among Filipinos. (“It’s funny how little coverage the show’s had in the Philippines, when it’s being covered by the New York Times,” he notes.)

Sure, Pacita bagged a “Ten Outstanding Men of the Year Award for Art” early on in 1984, but even that caused controversy, since few women had won the award at the time. “It ruffled a few feathers in Manila society,” says Pio. The TOYM was changed to “Outstanding Young Filipinos” for a while, until 1999 (“I think that’s because of her”), but its name has since reverted back to TOYM, gender be damned.

The Walker retrospective helps solidify Pacita’s recognition as a global woman artist — and an Asian woman, at that. After Minnesota, the show moves to SFMOMA in October, then to MoMA PS1 in New York and the Art Gallery of Ontario in 2024.

Curated by Victoria Sung, associate curator of Visual Arts at the Walker, the exhibition was developed with the Pacita Abad Art Estate, which is managed by Pacita’s husband Jack and wife Kristi (Pacita died in 2004) and Pio. It offers unprecedented access to archival materials, photographs, correspondence, sketchbooks and other primary sources. A massive 352-page catalogue edited and co-written by Sung places Pacita Abad’s work in historical context.

Sung had discovered the artist’s work from an earlier 1995 group show at the Walker, and asked herself, “Why didn’t I know about Pacita before?” That question led to a three-year process, putting the retrospective together. Sung has suggested Pacita’s (until now) marginalized position in the Western art world has something to do with being a woman of color; but it also reflects a hierarchy between craft art and fine art that has led to a kind of willful dismissal of work like Abad’s. Now, with a more global perspective, things make more sense.

Stepping back to see the bigger picture — even if it means leaving home — is advice Pacita gave her nephew early on when he considered an art career. “She actually told me, if I wanted to pursue this path seriously, I should consider getting the f*** out of Manila.” He took her advice.

Pio walks us through some of the highlights of the Walker show, beginning with her “Masks and Spirits” series. In this room, six trapunto pieces that formed a major installation in Washington, DC in 1993 are brought together for the first time in 30 years. These are stunning, colorful woven pieces: international in scope, but unmistakably Filipino in execution, theme and feel.

The exhibit moves into her “Immigrant Experience” works. The artist’s iconic trapunto “LA Liberty” “kind of occupies the center of the room, almost like a center of gravity,” says Pio, but it also includes one of her earlier paintings, “Flight to Freedom,” a 15-foot-long painting that depicts Cambodian refugees and the Thai-Cambodian border.

The next room includes her “Abstractions” and documents her experiments with textiles, along with archival material, photographs and news clippings. The final room (“the room that sort of blows everyone away, I think”) brings together most of Pacita’s underwater trapunto works: huge, 4x5-meter pieces depicting the Philippine undersea life. Some of these large works were shown at an MCAD exhibit in 2018, says Pio. “We’re very lucky the Lopez Museum has loaned it for this tour.” The centerpiece is a huge work depicting an octopus fighting a shark.

“So it just ends with this powerful immersion into another side of the Philippines,” Pio concludes. “What I find interesting is the underwater series is Pacita’s most concentrated depiction of the Philippines — it’s not the masks, it’s not brown bodies, but it’s insisting on looking at the country in a very different way by going underneath the surface.”

* * *

“Pacita Abad,” organized by the Walker Art Center, with support by the Henry Luce Foundation and the Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts, continues until Sept 3.

Visit walkerart.org for more information, or contact Rachel.joyce@walkerart.org.