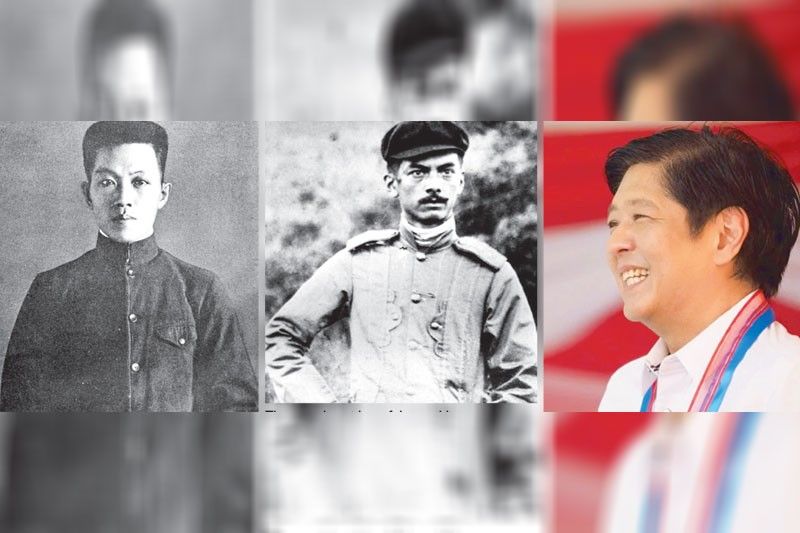

Aguinaldo, Quezon, Marcos: The ‘Long Now’ in art and culture

What better place to contemplate what’s next for art and culture in the era of Ferdinand Marcos, Jr. than in the historic town of Baler where two other presidents, Emilio Aguinaldo and Manuel Luis Quezon, would loom so large?

In more ways than one, Baler also happens to be a microcosm of that which blesses and ails the Filipino body politic in these fields and, yes, even in media. It’s also a parable of what happens next with a change in fortune, or in this case, the transfer of power from one regime to the next.

Baler is the place where 50-odd Spanish cazadores holed up in the tiny church of San Luis, withstanding a horde of machete-wielding bolomen plagued by what appears to be that distinctively Filipino and tragic trait of being overly patient.

On the other hand, the Spaniards were led by officers who likewise possessed the national character of bravura, the kind that had led them to the ends of the earth in the first place to establish an empire more than 300 years old.

The response of the first commander was simple: he locked himself and his men into the church and settled in for a siege, expecting it to end in just a few weeks. In fact, he would hang on to the notion of an undefeated Spanish empire for almost a year. The men he led were composed of the bullheaded and disbelieving — who were thinned out by a few deserters but were mostly men who became sick at heart (and therefore frail of body) because they were staunch supporters ofthe old order.The Spanish trapped in Baler refused offers for honorable surrender, denounced the newspapers that headlined their country’s defeat as the 19th-century equivalent of "fake news,” and dismissed emissaries from Madrid simply as local mestizos disguised as proper officialdom.

The katipuneros would respond to this obstinacy by pummeling the church first with cannon made of coconut trunks, and then finally from artillery brought in from Intramuros, all to no avail. They would try all kinds of attacks, including setting fire to the baptistry, in the process killing off the men who were most sympathetic to their cause who happened to be jailed there.

This may seem like a familiar scene from the novels of Garcia-Marquez for those staring into a future with a new dispensation for the next six years. Defeat, after all, is always a bitter pill to swallow, then as now; and one can recognize in the caged cazadores, living on squash (unsalted, to their horror), carabao flesh, and ferns pulled out from the roadside, those who have been disappointed by historical outcomes.

However, when both sets of soldiers had woken up one morning — one led by a young revolutionary called Teodorico Novicio Luna, distantly related to the famous brothers Juan and Antonio Luna; the other by a peninsulare with the name of Saturnino Martin-Cerezo — it was not one nor the other who had triumphed in the grander scheme of things but an unexpected new army, the American. The Yankees had just steamed into Manila Bay and simply taken over; and then finally, as the final blow, put pen to paper with the Treaty of Paris to make it official.

In mid-1899, or on June 30 to be exact, Aguinaldo seemed to have taken pity on the Spanish stragglers, realizing they were of no account in a new war against a new foe, and had them freed: “Not as prisoners of war,” as the Spanish Ambassador was quick to point out in his memorial speech, “but as friends.”

It is precisely at a similar moment, as one historic event leads to another, that a careful look at what surrounds us allows us to see more clearly what lies ahead.

Baler, like the rest of our cultural touchstones, is at a critical crossroads, between the rich Tagalog plains of Nueva Ecija and the rugged Ilocano landscape; between the ocean and the mountains. It is in the middle of a breathtakingly beautiful landscape; not the predictable sunlit spectacles of the Amorsolo lowlands but of the rich, deep greens of Hidalgo’s elusive Philippine period, filled with glass-like, dark rivers, towering palms and giant bamboo groves. It has the look of the unspoiled and the primeval, its tall cliffs and canyons covered with elephant-ear-sized leaves and mammoth fronds. The forests are so impenetrable, in fact, that they are home to an ancient headhunting tribe called the Ilongots who have their own rituals, customs and beliefs; and worship on what is protected ancestral lands.

The Pacific Ocean pounds incessantly beside Baler, underlining its impossible isolation. One is led to wonder how intrepid must have been a boy named Manuel Quezon to make his way to Manila, and from thence, to become Aguinaldo’s aide-de-camp precisely at the time of the Baler siege in 1899. (In an ironic turn of events, he would defeat the man he once served in the country’s very first presidential elections of 1935, trouncing Emilio Aguinaldo with a landslide vote of over 60 percent, foreshadowing Marcos’ own victory this year.)

Entranced by the Marcos win — and the prospect of the appearance of his newly appointed Tourism Secretary, Christina Garcia-Frasco — the mayors of all the towns of Aurora turned out in record numbers for the commemoration of the Baler Siege. The National Historical Commission estimates that the tentpole event has literally put the town on the map, propelled by the strong hand of Senator Edgardo J. Angara, who authored the bill to mark it. His son Sonny, also a senator, announced that the local economy had been so energized by this act that almost a million tourists arrived each year, pre-pandemic, which had leapfrogged from just 15,000 two decades ago.

What does this mean for the future of Philippine art and culture, or even tourism and the local economy for that matter? The study of history may well be the very key to unlock all of it.

For instance, a review of the new president’s own legislative history reveals that he is interested in teachers, libraries, climate change, chemistry (hydrogen) and — yes, science. All of these are bookish; all require the long view; all have a perspective that takes several years, in some cases, even decades. His avowed interests in agriculture — and wind energy, which he pioneered — indicates he will thus be interested in the flora and fauna, rivers and shores, in short, the stuff that Baler and thousands of towns across the Philippines are immensely rich in.

A few years ago, Jeff Bezos — a man who has no problem reimagining the future — came up with the astounding notion of the “Clock of the Long Now” or the “10,000 Year Clock.” It was designed to cultivate long-term thinking and is currently being built to tick once a year and to chime only once every millennia. Located in the depths of a mountain, it will have anniversary rooms to celebrate its first year, its 10th, 100th, 1,000th and 10,000th anniversary. It will be literally history in the making, intended for all of us to revere it, for in its lifespan will be housed the unpredictable and the unimaginable.

Politics has a way of foreshortening the cultural horizons to six-year doses; but if the lessons of Baler and Aguinaldo, Quezon and Marcos are to be taken to heart, then what remains should be a steadfast commitment to this “long now,” to a history-making future that will always and finally include that unexpected.