Beyond business, are alt-proteins better for the planet and people?

Second of a two-part special report on alternative meats in the Philippines. Read Story 1 here.

MANILA, Philippines — For yoga teacher Nancy Siy, having alternative proteins in the Philippines means vegans like her have a variety of options and makes it easier for people who want to embrace a healthier and more sustainable lifestyle.

"I think of plant-based meats or alternatives that are coming out now as a good option for us in terms of variety, in terms of choice, in terms of convenience," she said.

But the limited alternative protein options in groceries or convenience stores did not stop Siy from going vegan more than a decade ago. She has been a vegan and animal rights activist since 2009.

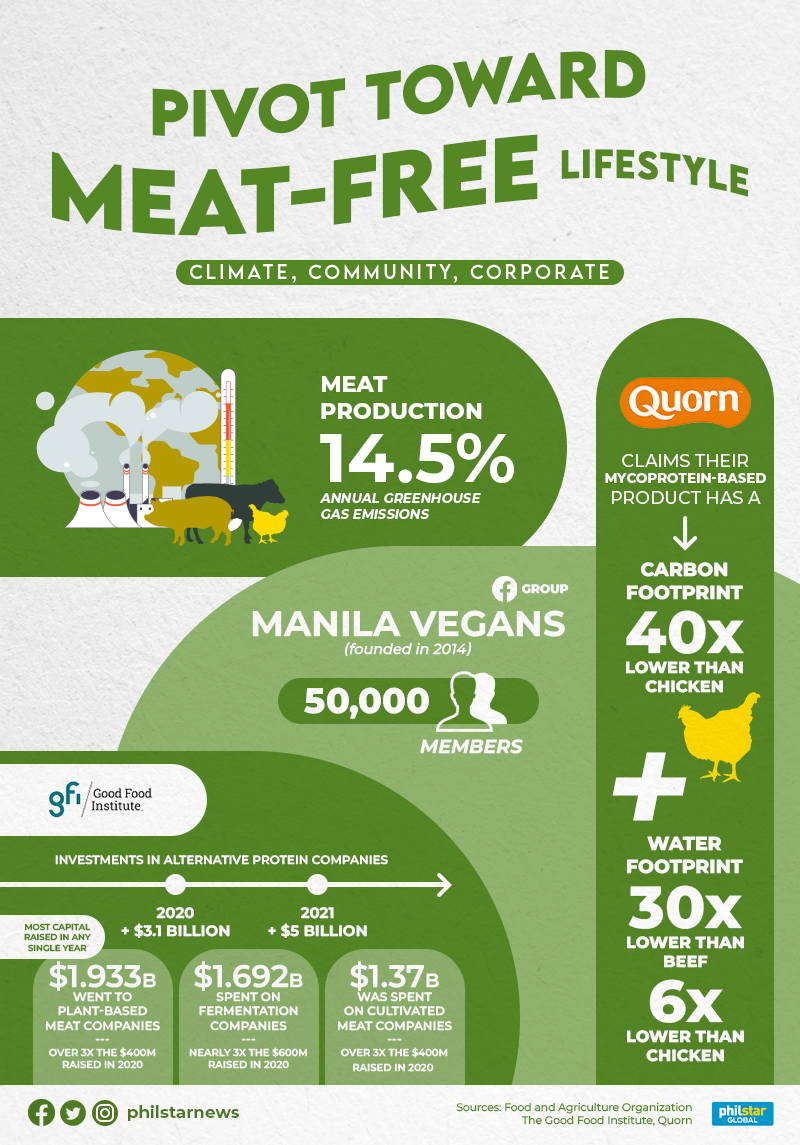

In 2014, she founded Manila Vegans, which now has over 50,000 members on Facebook. According to Siy, the group has evolved from focusing on what meals to prepare to understanding the commitment to animal liberation.

So while she viewed the availability of alternative proteins as a welcome development, Siy stressed that faux meat products are not the solution to speciesism, or the prejudice based on species, especially discrimination against animals. Vegans like Siy do not consume meat or buy animal products for ethical and moral reasons.

"Veganism comes from the rights approach. It’s tied to justice. It’s tied to equality. It’s tied to respecting animals. But eating plant-based [food] could just be about health, or even the environment, or even if someone doesn’t care about animals per se," Siy said.

In this 2019 file photo, backyard-grown pigs roam a community along the Kaliwa River in Quezon province.

But makers of alternative proteins—either plant-based or fermented or cultivated directly from cells—are not primarily targeting vegetarians or vegans like Siy.

"We cannot expect anyone to immediately shift. So we were trying to encourage, you know, flexitarians, consumers who are swapping their meat-based products, or whatever animal-derived products with plant-based because this is an investment in their health. This could be for environmental sustainability or animal welfare reasons," said Nikki Dizon, general manager of Century Pacific Food, Inc. (CNPF).

Quorn Philippines marketing director Irish Tanchua said it is the mission of the alt-protein brand to make it easier for consumers to "choose good" although, of course, it is up to consumers to decide for themselves what "good" is.

Shift to alt-meat

Imelda Angeles-Agdeppa, director of the country’s Food and Nutrition Research Institute (FNRI), said that shifting to alternative proteins can be challenging because animal meat has a “strong cultural and gastronomic significance” in the Philippines.

“Meat is considered an important part of the meal, culturally and as a source of nutrients. Now, shifting to alternative meats like plant proteins needs consumer education. And there should be a strong favorable message in order for them to accept [alternative proteins] across population groups,” she said.

According to the 2018 to 2019 Expanded National Nutrition Survey of the FNRI, fish, meat, and poultry were consumed in the Philippines in the second largest quantity at 665 grams per day, contributing to almost a fourth of the total mean consumption of households.

Cereals and cereal products such as rice were consumed in the largest quantity, contributing to 40.2% of the total mean household food intake in a day. Meanwhile, vegetables had the third highest consumption at 468 grams per day, or 15.5% of the total food intake.

Plant-based proteins are a source of vitamins, minerals, and antioxidants. Plant-based products can also be beneficial for weight management, and may help prevent cardiovascular disease and hypertension.

However, some plant-based proteins contain added sodium. "The biggest problem in consuming plant-based products is the sensory property. They cannot mimic or copy the flavor, color and texture," said Casiana Blanca Villarino, a professor at the Department of Food Science and Nutrition of the University of the Philippines Diliman who studies alternative proteins.

People in the Asia Pacific have been eating plant-based proteins for thousands of years and have learned to flavor foods such as tofu and Indonesian tempeh, which are both made from soybeans.

But the newer "plant-based products tend to contain more additives and flavorants to mask the undesirable sensory properties. So there’s more salt," Villarino added.

Better for the planet

Under the tagline "Helping the planet one bite at a time," Quorn claimed the carbon footprint of its mycoprotein is 40 times lower than beef and six times lower than chicken. Its carbon footprint figures are certified by third party Carbon Trust.

According to the company’s footprinting results, the carbon emission of its products in the Philippines such as the 300-gram mince and pieces was measured at 0.32 kgCO2e (kg of carbon dioxide equivalent).The figure considered emissions right up until the end of the product’s life, including storage, cooking, and disposal of packaging.

Quorn also claimed in its comparison report that the water footprint of its product is 30 times lower than beef, and six times lower than chicken.

CNPF, meanwhile, does not have data on the amount of emissions across all of their operations, supply chains or consumer waste. The base of its unMEAT products—non-GMO soy—is sourced overseas, primarily from China.

Soy—the base of many alternative proteins—is among the plants often monocropped. While monocropping provides a more profitable way to farm, the technique leaves the soil weakened and often pollutes groundwater supplies.

Dizon said the company is trying to source ingredients from local farmers to reduce its carbon footprint further. She, however, stressed that "it is still a challenge" because not all ingredients are available locally and if they are available, the prices are not competitive.

Nevertheless, experts said that widespread adoption of alternative proteins can play a vital role in tackling climate change.

"The ambitious climate targets that are needed to avert environmental catastrophe are not achievable without completely reimagining the way we produce steak, pork, and chicken," said Mirte Gosker, acting managing director of alternative protein think tank Good Food Institute Asia Pacific.

In a report released in April, the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change said that emerging food technologies such as cellular fermentation, cultured meat, and plant-based alternatives to animal-based products as well as controlled environment agriculture can bring "substantial reduction" in direct greenhouse gas emissions from food production.

"These technologies have lower land, water, nutrient footprints, and address concerns over animal welfare," the United Nations climate change panel added.

Plant-based for fewer pesos

Gosker said that accessibility and cost are key hurdles for consumers who want to incorporate more alternative proteins into their diet. She stressed that allocating resources aimed at accelerating technological advancements can drive down production costs and help alternative proteins achieve price parity with their conventional meat counterparts.

But vegans and those embracing plant-based diets do not have to spend hundreds of pesos for a meat substitute that will suit their lifestyle. Veganism does not have to be expensive, according to Siy, who said that adobong kangkong or fried tofu are readily available.

Because meat has always been expensive, lower-income Filipinos usually have diets with less protein. They have also long learned to make filling meals with less meat even before alternative proteins—which are not as accessible and affordable for them—became available.

According to the FNRI survey, rural households generally have a higher intake of rice, starchy roots and tubers, sugar and syrups, vegetables, and fruits compared to urban households. Meanwhile, families in urban areas generally have a higher intake of meat, fish, poultry, eggs, milk, and fats and oils.

Poor households also consumed more carbohydrate-rich foods, while wealthier families had higher consumption of protein-rich foods.

In Lupang Ramos, a farming community in Dasmariñas in Cavite, residents get by through the crops they grow in the backyards.

Nobody went hungry in the community even during the pandemic that restricted the movement of people, residents said, sharing they even had enough to share with other villages affected by the lockdowns.

One Saturday afternoon in June, residents of Lupang Ramos gathered to showcase and eat the nutritious dishes that helped them survive the pandemic: laing (taro leaves cooked in coconut milk), corn and malunggay (horseradish) soup, ginisang munggo (sauteed mung beans), fried eggplant, ensaladang talong (eggplant salad), and patties made from puso ng saging (banana flowers).

"If you have banana, cassava, gabi (taro), camote tops, you can overcome hunger," said 47-year-old mother Nanette Melendrez.

Growing crops as a community is also a form of empowerment and an assertion of their right to cultivate the land. The 372-hectare Lupang Ramos, sandwiched between commercial and industrial estates, has been a subject of decades-long agrarian disputes.

In 2017, residents who are part of the Katipunan ng mga Lehitimong Magsasaka at Mamamayan sa Lupang Ramos (KASAMA-LR) reclaimed patches of land in a bungkalan activity, or the collective tilling of land.

Through dialogues and lobbying, the community managed to convince the Department of Agriculture to send a tractor for members of KASAMA-LR to use in their community planting areas.

"We are continuing this struggle for the next generation… The local government should see the importance of preserving Lupang Ramos and other agricultural lands in Dasmariñas to achieve food security," KASAMA-LR spokesperson Miriam Villanueva said.

Potential solutions

There is no doubt that alternative proteins, despite their benefits, cannot be a silver bullet for environment challenges, climate change, and even food security.

The world’s population is expected to reach 9.7 billion by 2050 and could peak at nearly 11 billion around 2100.

For the Food and Agriculture Organization, alternative proteins are potential solutions to problems confronting the planet and its people.

GFI Asia Pacific’s Gosker also said that plant-based proteins provide a "clear alternative that is dramatically more efficient to produce and scalable to meet our growing population."

"Across rising economies in Asia, warning lights are flashing bright red for the future of industrial animal agriculture. Conventional meat production is ill-equipped to handle the escalating regional pressures of skyrocketing protein demand, increased climate disruption, land and water scarcity, and threats of viral outbreaks," Gosker said.

"Business as usual clearly cannot continue, which is why forward-thinking stakeholders from both public and private sectors have begun to rally around more sustainable protein alternatives, including plant-based and cultivated meat," she added.

--

This article is part of the Earth Journalism Network’s special collaborative project on One Health and meat in the Asia Pacific entitled “More Than Meats the Eye.” It brings together eight media outlets from different countries and more than a dozen reporters to cover the impact of meat on animal, human and environmental health in the Asia-Pacific region.

- Latest