Displaced and locked down in same year, Taal Lake folk face bleak Christmas

MANILA, Philippines — Christmas season in “Pulo”—what lakeside communities call Taal Volcano Island—just like in other Filipino communities, is marked by noisy revelry: traditional caroling, karaoke sessions, Christmas parties and Noche Buena feasts.

“We’d have an exchange gift and, of course, we’d drink,” Maria Elenita La Luz, 32, said in Filipino, chuckling, as she walked around the village where she grew up and started her own family.

But this Christmas, there will be no huge party for La Luz or any of her neighbors. Not only because the government has banned caroling and discouraged gatherings because of the coronavirus. But more so because villages on the island are now empty.

Celebrating the country’s biggest holiday will be a lot different and more difficult for former residents of Pulo nearly a year since Taal Volcano erupted and belched out ash that covered everything in a thick blanket of gray, rendering homes uninhabitable and wiping out their livelihood.

"We didn’t expect that we’d lose our way of life in the blink of an eye," La Luz said.

The Sunday that changed their lives

On the afternoon of January 12, the picturesque volcano in the middle of a lake in Batangas province suddenly woke up from its deep slumber, spewing a kilometer-high plume of ash and triggering a series of earthquakes.

It was supposed to be an ordinary Sunday for La Luz, a tour guide at a resort in Talisay town, which is billed the “gateway to Taal Volcano.”

She was accompanying tourists when earthquakes became more frequent before noon. Her guests were told to stay on the boat as people rushed to leave the island, grabbing only a few of their possessions.

While explaining the perilous situation to her angry guests, La Luz was messaging her family, telling them to cross the lake as soon as possible.

When they reached the mainland, Taal—the second most active volcano in the Philippines—began ejecting ash into the sky.

Thousands of residents from Pulo as well as those in areas within the 14-kilometer danger zone were ordered to evacuate.

At the time, Taal reached the fourth of a five-tiered alert system, which meant that a hazardous eruption was possible within hours or days. Affected residents were brought to evacuation centers and schools in other parts of Batangas and in the neighboring province of Cavite.

“We weren’t able to bring anything, not even clothes or important documents. We were caught by surprise. At the time, we thought we’d be able to return right away,” Sarah Jane Aala, 30, said.

'No man’s land'

Hardest hit by the eruption were the residents of Pulo, which was home to families dependent on fishing and on tourism. Ash transformed the volcano island into a wasteland.

San Isidro, a village on the island and administratively part of Talisay, was once bustling with foreign and local tourists. In late November, it still looked like a ghost town. Dead trees were everywhere. Collapsed houses lay empty.

Only a handful of people were there—fishermen who tend fish cages in the lake. They have to leave before sundown.

Residents have been barred from living on the island following the January eruption. But even before that, Pulo had long been declared off-limits to settlements due to volcanic activities.

In the neighboring village of Santa Milagrosa, the situation was better. Things looked normal, save for deserted homes and a feeling of stillness. La Luz believes the village’s patroness, protected the community.

Since March 19, the status of Taal Volcano has been at Alert Level 1 after volcanic earthquakes and surface activity at the main crater decreased.

Although it is the lowest alert level, the Philippine Institute of Volcanology and Seismology advised the public that sudden steam-driven or explosions, volcanic earthquakes, minor ashfall and lethal accumulations or expulsions of gas could happen within the volcano island. People are still prohibited from entering the danger zone within four kilometers of the volcano.

From the ashes

The island and the lake form part of the Taal Volcano Protected Landscape (TVPL), a protected area by the virtue of Proclamation 923 signed by then President Fidel Ramos in 1996. TVPL is managed by the Protected Area Management Board (PAMB), which is composed of heads of government agencies and local chief executives.

Noel Recillo, Batangas province environment and natural resources officer and the concurrent protected area superintendent, said the PAMB will still have to discuss possible rehabilitation plans for the volcano island when they revise the TVPL masterplan next year.

The Biodiversity Management Bureau, an attached agency of the Department of Environment and Natural Resources, plans to do regular assessment to determine the economic value of ecosystem services—the value or benefit that the environment has for people— within the protected area that were lost after the eruption.

“Our end goal is input to management: what are the primary resources to focus on? [Is it] conservation, protection? What are the areas that [have] to be used for economic benefits as far as people are concerned?” Ricardo Calderon, BMB director, said.

He added the government is also focused on maintaining the ecological integrity of Taal Lake—home of the endemic tawilis (Sardinella tawilis), which has been listed as an endangered species. Even prior to the eruption, the lake had already been facing various threats: the proliferation of fish cages and pollution from aquaculture facilities and lakeside communities.

Calderon sees no problem with the resumption of ecotourism activities such as trekking on the island post-eruption as long as state volcanologists deem it safe.

Scientists from the University of the Philippines and the University of Santo Tomas also conducted preliminary research expeditions to the desolate volcano island and the lake in a bid to aid landowners, communities and local governments manage and sustain resources from the protected area.

Flora and fauna experts would look into the revegetation of the island, while geologists would study the volcano's history. Freshwater biologists would evaluate the post-eruption ecology of tawilis and other organisms in the lake.

“We are really dealing with a group of concerned citizens, stakeholders from the surrounding lakeshore towns in Taal Lake on what they should do to the lake and the volcano. Even before the eruption happened, the lake had already been beset by many issues,” Rey Donne Papa, one of the participating scientists, said.

The program was an initiative of the FAITH Colleges (First Asia Institute of Technology and Humanities), which is crafting a management plan that will develop a property within the volcano island into a nature conservancy area.

“We are still in the scoping stage but the indicative direction leans toward two strategic concerns: how can the foundation contribute to the sustainable management of the land and water resources of the Taal Volcano Protected Landscape? How can we contribute to the disaster preparedness mandate of LGUs and the need of local communities to understand the risks posed in and by their natural environment,” said Ed Coronel, executive director of FAITH Botanic Gardens Foundation, Inc.

Inundated communities

Lakeside communities are also facing a different problem months after the eruption: inundation

In Agoncillo town, several houses have been submerged as waters from Taal Lake creep inland.

Taal Lake also swallowed a portion of a road in the village of Subic Ilaya, cutting off road access. People pay P20 to cross to the other side on rafts pulled by residents wading through the chest-deep water. The rafts can ferry motorcycles and tricycles but heavier vehicles need to take a detour.

“My house survived the eruption but the flood reduced it to rubble,” Arnold Alilio, a resident of nearby Banyaga village, said.

He said the January eruption and the earthquakes altered the topography in the area, and recent typhoons made the situation worse.

The Philippines was hit by consecutive strong storms between late October and early November: Typhoon Quinta (Molave), Super Typhoon Rolly (Goni) and Typhoon Ulysses (Vamco).

Agoncillo is within the designated 14-kilometer danger zone and is among towns severely affected by the eruption. Around 1,500 houses were destroyed by the earthquakes and the ashfall, while at least another 3,000 were left partially damaged.

The eruption also created ground fissures in the town, Agoncillo Mayor Daniel Reyes said

“[The flooding] is due to the deposited ash in the upland areas and fissures so when the rain pours, the soil cannot absorb the water anymore. Unlike before when the soil absorbed the water, now it flows to the creek, causing flashfloods,” Reyes said, citing the study conducted by the municipality.

“Once it rains, or when there’s a cyclone, [flooding] will happen,” he said. The municipality plans to build a road that will bypass the flooding.

Waiting for help

Some residents of Pulo were able to build new homes in Talisay. Others are staying with their relatives on the mainland. But many Taal eruption survivors are still in evacuation centers across the water from the island.

La Luz’s family, along with some 40 other households, is seeking refuge at Aya Evacuation Center inside an elementary school in Talisay. Around 23 families stay in a large room partitioned only by blankets.

Near the town’s center is Tumaway Senior High School, where some 126 displaced families are staying.

Shela Marie Gaduyon’s family and around 50 other households live in an unfinished two-story school building.

There is barely enough living space in Gaduyon’s makeshift home—which she preferred to call a “boarding house”—for her, her husband and her seven children along with their belongings, which are mostly donated.

“We can’t sleep properly here. It’s really difficult when you’re not living in your own home. We pity the children because it gets really cold early in the morning,” Gaduyon said.

Before the eruption, residents of Pulo thrived as tour guides, horse tenders, fishers and farmers. La Luz could earn P500 ($10) a day. But this amount does not include the tips she received from tourists, which could go as high as P2,000 ($41) if they were “very generous.”

But the eruption killed the tourism industry on the island, leaving many jobless. Men are now working in construction sites, making only P370 ($7.75) a day. Others are still fishing or feeding tilapia in fish cages.

Women, meanwhile, are left in evacuation centers to take care of their children.

“It’s easier to earn money in Pulo unlike here. If you don’t work, it’ll be hard for you to survive because you have to pay for everything. Being hardworking is the only thing you need in Pulo to get by,” Aala said.

Life, for the displaced residents, is tough. But they have no choice but to endure their current circumstances as they wait for the local government’s housing project for them.

They had been told there is a plan for their relocation, but that was before the pandemic happened. They have no idea how much longer they will have to wait.

The Talisay local government has yet to respond to Philstar.com’s request for comment on its plans for the evacuees.

Uprooted from the seaside

In a mountainous area in San Luis town in Batangas, an hour and a half away from Talisay, members of an indigenous Aeta community are rebuilding their lives. They used to reside by the sea but the eruption of Taal prompted them to relocate upland.

Zosimo Magtibay, the tribe’s chieftain, said they had already planned to transfer to the land where they are currently living, which is a 15-minute trek from the foot of the mountain in the town’s Barangay Banoyo, even before the eruption.

But the volcanic unrest earlier this year hastened their planned move, leaving them without shelter, water and electricity.

Fortunately, help from the local government and from private donors poured in, providing them construction materials, food packs, solar panels and other basic necessities.

A lot has changed since January, Magtibay said, as they were able to construct new homes, a learning center for school children and a community center, which also serves as their chapel.

Their community is still far from being complete: there is still no electricity in the area, making it a struggle for everyone, especially students in the tribe. The path to their village is still unpaved and unlit, posing dangers to villagers, especially at night.

Moving from seaside to upland also meant changing their source of livelihood. Men of the clan used to fish in Balayan Bay but their boats had been damaged. The women, meanwhile, made doormats.

“The difference [between living in the mountain and by the sea] is huge. When we’re in the lowland, we have many opportunities to earn money: we pick up plastic waste on the beach and sell them. Men venture out to fish. We also sell herbal products,” Susan Magtibay, the wife of the clan’s leader, said.

Members of their community now make a living by selling “anything that can be sold” such as vegetables and herbs. Some men work in construction, while others are paid to cut grass.

Despite the hardships that come with relocation, residents believe they are in a better place now.

Another crisis

Another disaster in the form of an unprecedented health crisis disrupted the lives of Taal survivors as they were adjusting to the shock of the eruption.

Two weeks after the volcanic eruption, health authorities in the Philippines announced the country’s first case of coronavirus disease.

In March, when they were starting to pick themselves up, the COVID-19 pandemic began to take a firm hold in the Philippines, prompting the government to impose stringent movement restrictions that have remained in place to varying degrees since.

Displaced residents were able to stock food, thanks to donations by various people and organizations before a strict lockdown brought the nation to a halt.

But fewer donations from the private sector reached them due to movement restrictions and the rise in COVID-19 cases.

“When the pandemic struck, donations stopped coming. Our husbands were not allowed to go out to work at the time. We were waiting for relief goods. Until now, nothing has arrived,” Gaduyon said.

There were times that the local and national government gave them financial assistance but they could not live off the occasional aid as the pandemic casts uncertainty on them.

Batangas has had 12,638 coronavirus cases, of which 574 are still active, as of December 23. It is one of the few provinces under general community quarantine although restrictions have been relaxed.

COVID-19 poses a threat to evacuees living in cramped temporary shelters. Fortunately, the two evacuation centers are still COVID-19 free. But maintaining a one-meter distance with others inside temporary shelters is almost impossible.

Communal bathrooms are also very risky, and with the sheer number of people staying at the centers, some have stopped working.

According to a UNICEF study in 2016, the lack of adequate access to water and sanitation “is likely to increase the vulnerability to violence”—specifically violence against women and girls.

It noted that “poor access to WASH services can lead to vulnerability, rape and assaults, and that fear of such assaults can prevent women and children from using sanitary facilities outside of the home at night.”

“Children can be vulnerable to sexual violence in school or when left at home while the mother is out to undertake WASH-related tasks,” it also said.

In interviews at one of the centers in Talisay, a mother said that she was worried about peeping toms when her daughter bathes.

Teenage girls at the center were also observed going to the communal bathroom structure in groups, with some standing guard while one of them used the facilities.

Added responsibility for parents

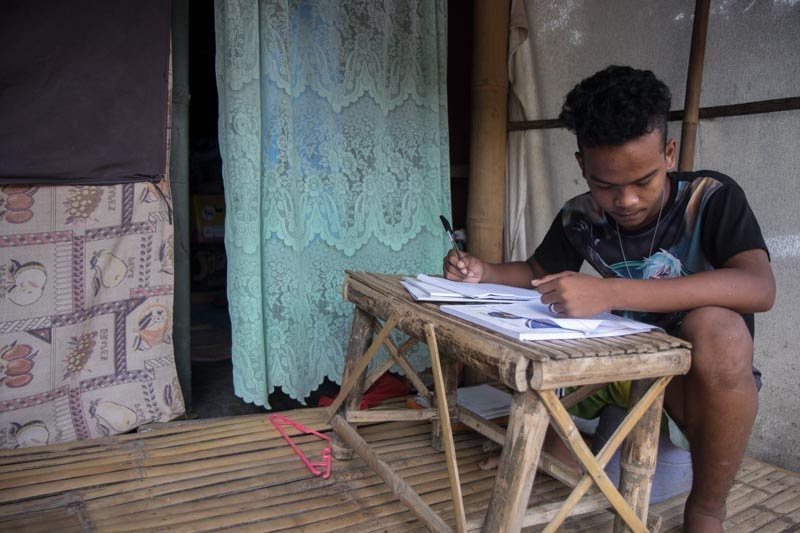

The health crisis also reshaped the idea of teaching and learning. President Rodrigo Duterte prohibited traditional face-to-face classes until a coronavirus vaccine is available in the country.

Students shifted to distance learning—a mix of printed or online learning materials or “modules,” online classes, and radio and television educational broadcasts—when classes began in October. Because poor families cannot afford to hire tutors, mothers, fathers and guardians now carry the responsibility of being co-teachers.

La Luz worked briefly in a factory after the volcanic eruption. But she had to resign to help her 15-year-old son with schoolwork, a job she is not trained to do.

“I want to focus on my son,” she said.

As in past calamities and crises, women bear the brunt of the disruption of not just the family’s livelihood but of their home life as well.

In an interview in 2016, Aimee Santos—now head of the gender program at the UN Population Fund in the Philippines—said that women in general are economically and politically marginalized.

“They carry multiple burdens in our families and our communities,” she said then, adding that women “[experience] more of the burden, more of the anxieties, more of the problems.”

They are expected to take care of the home but also to supplement the household’s finances when the men are idled by droughts or in the case of the Taal evacuees nearly five years later, by the pandemic.

They may also have to give up their own jobs to take care of their children.

Difficulties in distance learning

Ana Banaag, a teacher in San Luis, said modules are delivered to the Aeta community every Monday and are picked up by Friday.

Students who have questions about their lessons reach out to her through Facebook Messenger or text message but not everyone has access to gadgets. But if they are still having difficulties, Banaag would come over and help them.

“It’s difficult because the majority of the students here are under a basic literacy program so face-to-face approach is really needed. Giving them modules is not enough if they could not read these,” she said.

Some parents in the tribe also supervise their children’s classes while studying at the same time. Dela Luna, a 35-year-old working mother, is currently enrolled in the Alternative Learning System program, which allows school dropouts to complete elementary and secondary education outside the formal school system.

“I work as a house help by day. At night, I would help my children in their classes, while also working on my module. It’s tough,” she said

Bleak Christmas

For many Filipinos, the eruption of Taal in January felt like it happened a long time ago. After all, a lot has happened in the country since: the ongoing COVID-19 crisis, lockdowns and back-to-back strong typhoons.

But Taal survivors continue to deal with their trauma and the disaster’s aftermath, now aggravated by the pandemic.

Gaduyon said they could not do much except wait for the government to help and provide them the much-needed housing.

“We are asking for help because we’ve been here for many months, we’re nearing a year here but nothing has happened yet,” she said.

La Luz has since returned to her job as a tour guide after the local tourism office allowed the resumption of boat rides around Taal Lake. It’s a welcome development but the road to recovery is still far from over.

She and other displaced residents would celebrate Christmas inside evacuation centers. It would not be as joyous as it used to be when they were living on the island but they would still try to enjoy it, she said.

She has many wishes for Christmas but at the top of the list, no matter how impossible it is at this point, is settling again on Pulo.

“It’s always a part of my prayer: for us to return to our old lives on the island, for our hometown to regain its beauty,” La Luz said. — with Efigenio Toledo IV and Jonathan de Santos

Reporting for this story was made possible through support from Internews’ Earth Journalism Network.

- Latest

- Trending