Philippines sends fewest workers abroad in 24 years even sans jobs at home

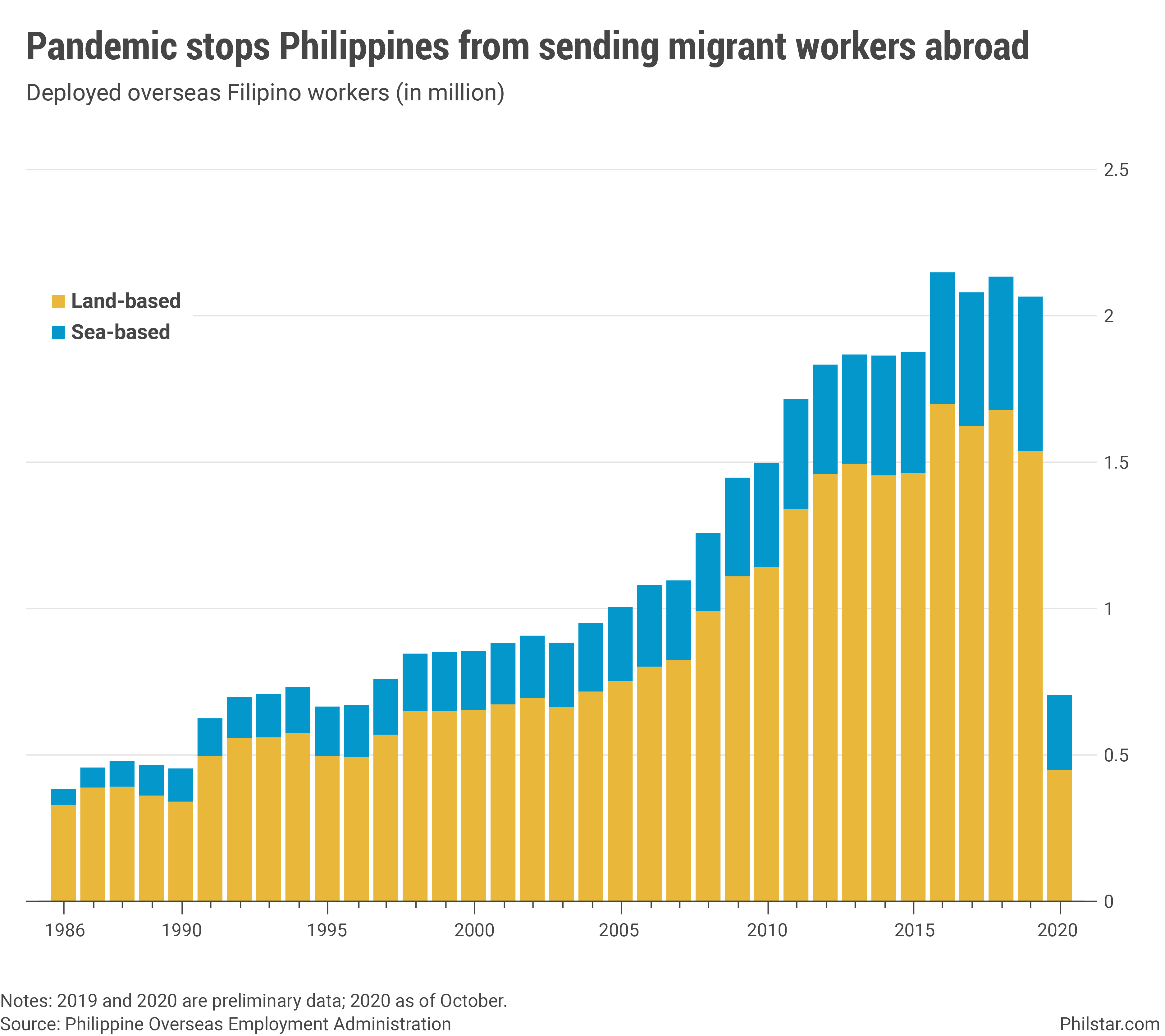

MANILA, Philippines — Even with no jobs at home, hiring of Filipino migrant workers is on track to its lowest level in nearly 3 decades due to sprawling lockdowns that stopped deployment, putting the Philippines’ main dollar source at risk of future decline.

From January to October, 693,237 overseas Filipino workers had been deployed, plummeting 60.8% from same period a year ago, preliminary data from the Philippine Overseas Employment Administration showed.

The latest tally is running at its lowest since 1996, a year before the Asian financial crisis, when yearend deployment registered 660,122. With only 2 months left to record, OFW placement is on track for its third slump in 4 years.

“The decreased deployments do not surprise authorities. Hurt also by this development is the recruitment industry, with reports that some of them have closed operations,” Jeremaiah Opiniano, executive director of the Institute for Migration and Development Issues, said in an online exchange.

The impact of lower OFW deployment is slowly revealing. Cash remittances from migrant workers declined 1.4% from January to September, hitting households dependent on these earnings hard, with their consumption down 8.7% in the same 9-month period.

Dismal deployment is also the reason analysts have remained pessimistic about remittances’ future trajectory despite inflows regaining some ground since June. The central bank believes the altruistic nature of inflows to families they support here would deliver the needed boost onwards, but Opiniano thinks OFWs are simply exhausting their savings.

“They had to send more now because the Philippine peso to the dollar appreciated from 50 to 48 during this pandemic! That alone, for me, indicates some measure of financial pressure and stress,” he said in an online exchange.

Alvin Ang, director of the Ateneo Center for Economic Research and Development, agreed and said “consumption (would be) slower” as remittances taper off in coming months. Consumption accounts for 70% of economic output, so further weakness on this front would only derail a rebound from 10% contraction in gross domestic product to date.

Re-migration or reintegration?

But in the long term, job losses among migrant workers are the bigger concern. As it is, OFW deployment is not going down because there are more jobs generated locally. In fact joblessness is still treading at record levels of 8.7% as of October, even as it already went down from a historic high of 17.7% in April.

Deployment is also not picking up despite economies reopening and government allowing health workers to fly out after prohibiting them to leave for months. Among those deployed as of October, land-based workers, which accounted for 63.8% of total, dropped a bigger 69% year-on-year to 442,071.

On flip side, the number of seafarers went down a smaller 28.02% annually to 251,616 after monthly deployment reversed back to growth from July.

Opiniano is surprised sea-based workers have recovered quickly despite cruise ships where most of them are employed halting sails when cities closed down. That said, rehiring of existing OFWs also got stunted, cementing a bleak outlook for remittances.

“New hires may not be able to remit right away since they may have borrowed money to finance pre-migration expenses,” he explained.

For the 320,000 OFWs displaced by pandemic, it’s hard to say for now how swift can they go back offshore, although better local jobs can prompt them to stay home permanently. “The infrastructure plan can create new jobs and in case those OFWs decide to stay, they will have more options,” Rong Qian, senior economist at World Bank local office, said in a briefing.

Labor export policy disrupted?

Policy-wise, Joanna Concepcion, chair at Migrante International, a labor group advocating OFW welfare, said the pandemic had only revealed the government’s problematic “long-standing policy” of exporting Filipinos. “(It) cannot guarantee long-term economic security for our migrant workers and cannot genuinely solve the economic and development problems facing our country,” she said.

The Philippine Overseas Employment Administration denied there is such a policy, even as it has persistently held job fairs showcasing overseas work opportunities. On top of that, President Rodrigo Duterte has pushed for the establishment of a sole agency to address OFW concerns, a move that would only institutionalize labor exportation only explored as band aid solution during the Marcos era.

“The Philippines cannot continue to be a remittance dependent country,” Concepion said in an email.

- Latest

- Trending