'Easy to overlook': Social amelioration lapses weigh doubly on PWDs, advocates say

MANILA, Philippines — Former radio DJ Victor Dax Jose will likely die without his medication.

Since he was diagnosed in 2017, he has wrestled to keep his chronic myelogenous leukemia—a rare cancer of the blood and bone marrow with a five-year survival rate 27.4% according to the US National Cancer Institute—at bay.

As a result, any sort of movement has been a chore at best, and he is forced to rely on Imatinib, a drug that keeps his white blood cells in check. He can walk straight on good days, but on most days he walks with a cane.

Now retired from the media industry, the 47-year-old lives with a disability and gets by on social security benefits and "no work, no pay" arrangements; typically working freelance writing or call center jobs from his condominium unit.

Like other persons with disabilities throughout the lockdown of Luzon, Jose reported to PWD groups that he was not given social amelioration aid by his barangay somewhere in Rizal province.

When he complained to the Department of Social Welfare and Development, he was referred to his local government unit—until the complaint landed back with the same barangay captain who denied him aid in the first place.

The captain then tried to give him P200 that— in his need, and after having walked to the barangay’s office—he was forced to accept.

As a consolation, a social worker at the Municipal Social Welfare and Development Office told him to wait for the social amelioration intended for OFWs. If any of them fail to pick their aid up, he could have it.

Left behind

Jose’s is one story among many, though government officials may say these cases are isolated and anecdotal.

Most advocates and PWDs disagree.

Nine weeks into the enhanced community quarantine, many of the disabled say they are still without aid, even as government documents show that social amelioration distribution has picked up after a lackluster and logistically unsound start.

The DSWD's social amelioration program is intended to assist indigents who were left sidelined and without income by the enhanced community quarantine, though the DSWD has placed most of the blame on LGUs themselves.

Over the past month, Philstar.com spoke with different disability alliances and federations across Luzon. In different cities and municipalities, the story of the PWD has been constant: they feel they are being left behind.

READ: Social distancing's victims: In a Luzon quarantine, the disabled are mostly forgotten

“We’re categorized and put under the microscope already as it is,” Jose says.

“Where’s the money that’s supposed to be for us, the marginalized? I’m not low income, I’m no income right now. I’m not only jobless, I’m also disabled. I was dumbfounded. This is a government-appointed social worker telling me to wait for someone else’s aid. It doesn’t make sense,” he says.

Two months since the enhanced community quarantine was first implemented, and the disabled still don't have many choices: if they observe the quarantine and stay indoors, they risk aggravating their existing conditions without proper healthcare, medicine, and aid, with many PWD families living in poverty exacerbated by no work, no pay arrangements.

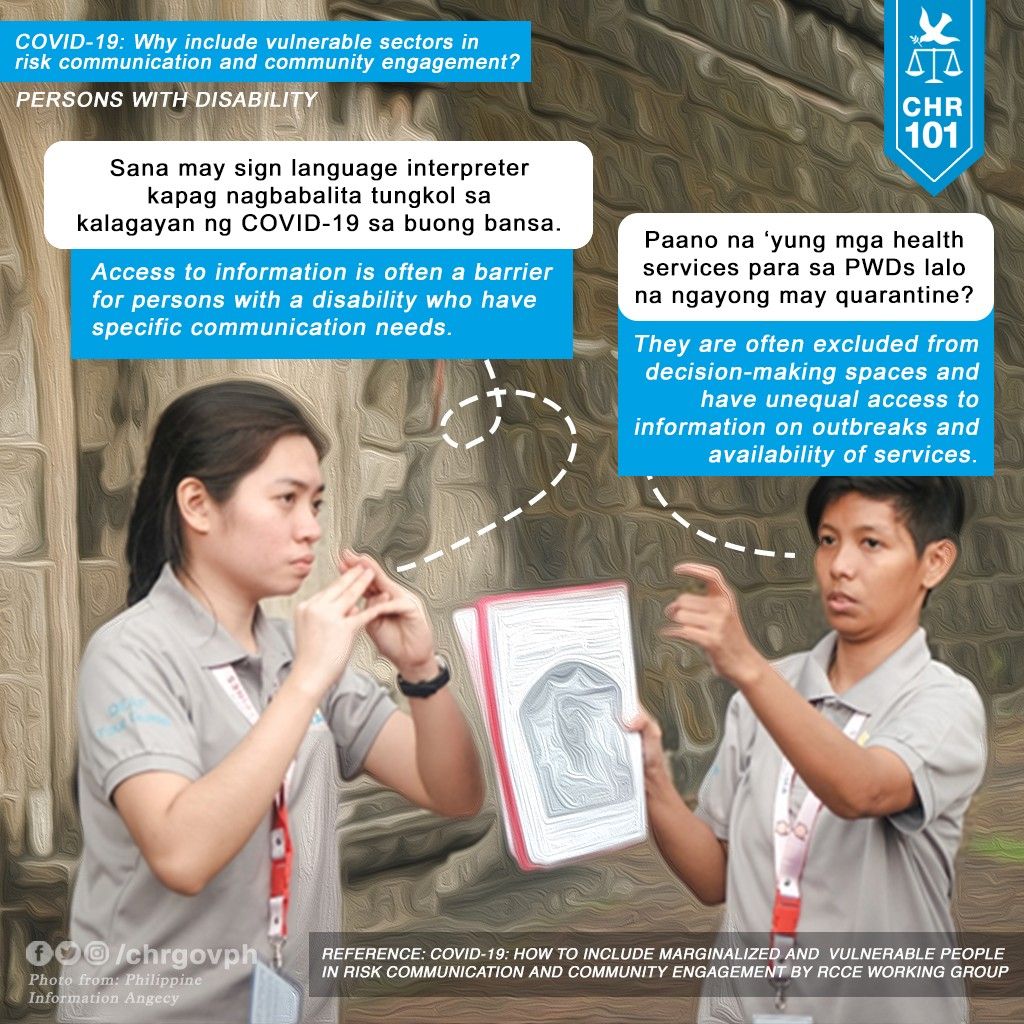

The Commission on Human Rights and the United Nations have both called attention to the sector, saying they are often left out of decision-making spaces in government.

The gritty indoors

According to Arpee Lazaro, president of the Angono, Rizal-based PWD Philippines, the discrimination and existing stigma towards the disabled plays a big role in the way their aid is rolled out for them.

“PWDs are thought of to be stupid and dumb, easy fodder for corruption. It is very easy to overlook the needs of the PWD because the local government and barangay officials don’t expect the PWD to complain and for their complaints to even gain the attention of their superiors,” he says in an online exchange in a mix of English and Filipino.

“My personal observation is that barangay captains think the disabled aren’t able to complain and that they aren’t voters. In the end it just boils down to what the citizen can give to the politician and not what the politician can give to the citizens. They will continue to step on the marginalized because they can,” he added.

In a separate phone call, Alex Mendoza, Quezon City Federation of Persons with Disability, Inc. president, says that his group had received many reports that the resulting uncertainty over hunger and income have triggered episodes of bipolar disorder and schizophrenia for those with psychosocial ailments.

Mendoza, who represents the sector as part of the city’s development council, is a registered PWD himself, having dealt with polio and ADHD for years.

“There have been many recent cases. They just aren't reported because you cannot go to the hospital, so you keep it to yourself. They should watch out for this. Everytime there’s a disaster, the people’s psychological well-being is affected and that is a given,” he says in English and Filipino.

“It is easier to be triggered. I know myself and I can feel it when something’s not normal. It's more depressing. When I am hyper, I cannot leave the house. I hope that I will be okay. I’m confined in a room in a small apartment. I can’t move as much as I want,” he added.

“The government seems to think that disaster management is all about giving food. The debriefing is always absent. They don't give therapy to the elderly," he says.

In a livestreamed discussion with Coalition for People’s Right to Health, Mendoza says: “In times like these, mental health issues are easier to trigger. Persons With Disabilities doubly experience the difficulties compared to people without disabilities.”

"Those of us who are well off are lucky, but PWDs in poverty, you can see the desperation. It’s pitiful. What choice does the sector have? The style of government right now, you can’t avoid corruption. The desperation is grave. Others start to become suicidal. But other people won’t feel that, especially the government. You can only see the physical, but a PWDs psychological well being is different. I didn’t think it would be like this, nobody could have expected that the effect would be like this," he adds in Filipino.

“I have ten tablets right now. I take one a day, so that’s ten days,” Jose says.

“I’m tired. Just thinking about it drains me out. I don’t think I’ll follow up on my aid. Most days I just stay in my room. It’s depressing.”

No data, ‘no problem’

Mendoza says that much of the desperation comes from the fact that complaints are hard to file and even harder to prove without proper data on PWDs.

The last known census on the disability community in the country was conducted in 2010, which tallied only 1.44 million of them nationwide.

Unable to lobby, the disabled have turned to social media groups and chat rooms, where the bulk of Mendoza’s monitoring takes place, to organize and ask for aid.

In a phone call, Emer Rojas, president of non-government PWD advocacy group New Vois Association and former sector representative at the National Anti-Poverty Commission (NAPC) says that a bulk of the complaints arose from the lack of information dissemination on the PWDs exempted from the social amelioration program.

“Some PWDs complain but they aren’t even registered. They should be qualified. The unorganized or unregistered PWDs in the household must be identified and given SAP of financial support,” Rojas says.

Lazaro agreed, saying: “It should still be understood that the SAP is primarily for the poorest of the poor.”

Rojas, a laryngeal cancer survivor who speaks through an electro larynx, says that his group hardly received complaints, though he admitted that New Vois Association’s membership included many senior citizens, who are more comprehensively documented in government databases.

"You will see, there is really discrimination. The seniors received a little. A majority of the sector got no aid at all. But it's hard to prove discrimination," Mendoza says.

PWD Philippines in an earlier exchange with Philstar.com said that the Department of Health once had a now-defunct national database for persons with disabilities.

The group said having a working database of PWDs could make all the difference in tracking the disabled and ultimately securing their rights.

“There are different SAP distribution channels which cause duplication since their data is not integrated into one database. It should have followed the Malasakit Center model wherein only one entity provides SAP to everyone to avoid duplication and seamless distribution,” Rojas added.

Due to the muddled rolling out of social amelioration funds, most groups rely on aid from their LGUs, barangays, and even private NGOs, particularly QC-PWD.

READ: Women with Disabilities Day passes with women, PWDs still facing hurdles in access and mobility

"Cavite is one of the most complained provinces. Makati is a different story. They will give all voters 5000 pesos. But that is on the condition that they are active voters," Lazaro said.

Miscommunication

Lazaro and Rojas say many complaints come from the assumption that all PWDs are qualified for the Social Amelioration Program, which they say reflects on the poor information dissemination on the part of both the Social Welfare Department and local governments.

As it stands, while PWDs are listed as beneficiaries under the social amelioration program, there are a number of exceptions, including PWDs who are also:

- Existing pensioners

- Government employees

- Overseas Filipino workers

- Public transportation drivers

- Private employees on 'no work, no pay' arrangements

- Pantawid Pamilyang Pilipino Program (4Ps) beneficiaries

- Employees on 'work from home' status

- Business owners

- PWDs with relatives having income prior to lockdown

- Solo parents with business or government employment

“Information on disqualifications is lacking. This may not have been widely circulated or some did not understand that there are disqualifications. The government must keep on repeatedly informing that only 1 SAP per household is allowed,” Rojas added.

Other government departments have been tasked with providing financial aid for some of the exemptions. The labor department, for example, had a financial aid program for displaced workers while 4Ps beneficiaries got aid through the conditional cash transfer program.

Rojas says that many complaints came from PWDs who were taken off the list because they failed to qualify.

Many of these, he says, were also because they were not registered PWDs with the necessary identification.

“Some PWDs or even vendors and drivers complained they did not receive any SAP. But a week later, actually some have received it but it was only delayed. The unorganized or unregistered PWDs in the household must be identified and given SAP or financial support,” he says.

He says the problem has to do with the much-delayed logistics of distribution, though he asserted, too, that PWDs who don’t receive aid at all are “isolated cases.”

READ: 'No consideration': In pain, PWD with walking ailment forced to personally claim aid at CSWD

In an earlier phone call with Philstar.com, 42-year-old Roy Moral, who suffers from ankylosing spondylitis that renders him unable to walk, said he sent his wife as a representative to claim his stub at his City Social Welfare & Development office.

After the latter came with the necessary documents, she was told that he was required to be physically present in order to claim his money.

They did not bother looking at the documents she brought, he says, because they needed him there so the office could take a picture of him being handed the money.

"The distribution, that's what should be changed. That's the problem for big barangays. It should be house to house, but it's not organized, so naturally a lot of people will complain. The database for the barangays should be updated too. They shouldn’t be made to line up," Rojas says in Filipino.

The Department of Social Welfare and Development has urged senior citizens and persons with disabilities to stay at home, saying local governments should find ways—including delivering the financial aid directly—to get government subsidies to their intended beneficiaries.

RELATED: Local governments urged to deliver cash aid to senior citizens, PWDs

"In the distribution of assistance, DSWD reminds our partners in implementation that payout should be done through door-to-door, especially for the senior citizens and persons with disabilities," DSWD spokesperson Irene Dumlao told Philstar.com after a PWD beneficiary had difficulty in receiving aid.

"If door-to-door is not possible, a healthy and abled-body member of the family should be allowed to receive the aid," she added.

‘Money for sustenance goes to disability’

Whether these are enough or not is another problem of its own, Rojas says, because the reference point of poverty comes with the assumption that what they have is enough.

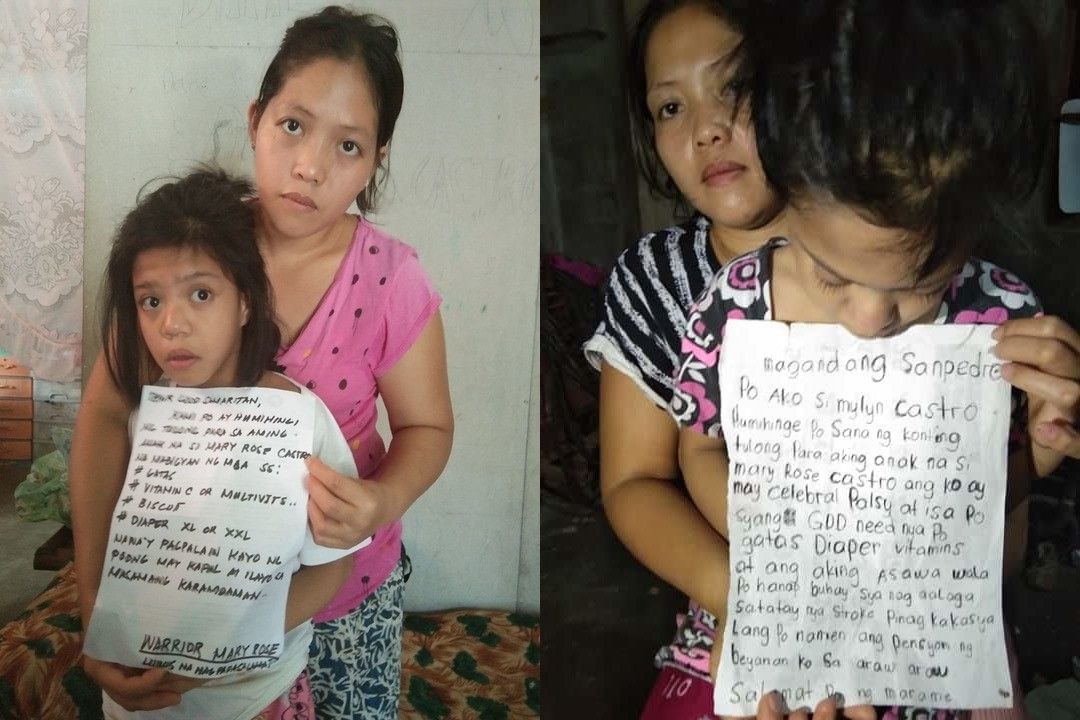

In the middle of the quarantine, Mendoza says, blind PWDs and people with cancer were forced to break quarantine to beg for aid.

While PWDs like Jose do receive funds elsewhere, the former DJ says all of his SSS money goes into buying the medicines that keep him alive. One box good for a month will cost at least P6,000 in the Philippines, he says.

“[Without meds] my white blood cells start shooting up steadily and lethally. Dying without a fight is something that bothers me a lot. These people were supposed to take care of me in my twilight disabled years,” Jose says.

One PWD non-profit that requested anonymity told Philstar.com that members of its Laguna-based organization have received aid: they were offered P800 from their barangays.

Once PWDs availed of this support, they are no longer qualified for SAP aid of P6,500.

“In our group chat for PWDs, they voice out their frustration. It's possible that the aid is not enough. Aside from food, thet need medicine. And they also have electric and water bills,” they say.

"They said: We'll just make do so it will be enough"

“The meds are the biggest negative. The money that’s supposed to be allotted for food, for my daily existence, goes to my meds instead. Before the virus, I could get hired for jobs and work from home. Now, nobody’s calling. So there’s no medicine, no income, no food on the table,” Jose says.

‘Gov’t making sure PWDs are served next time’

In a phone call, the National Council for Disability Affairs opted not to comment on the distribution of cash and material aid.

The NCDA is an attached agency under the DSWD, though its mandate is not that of an implementing body. PWD Philippines has said that its role was as a go-between.

Asked what PWDs with complaints over lack of aid should do, NCDA Deputy Executive Director Mateo Lee Jr. told Philstar.com: "Of course, I cannot say they should wait because aid might not come. They should first look to their barangays. Then, if that doesn't work, they can bring it to their mayor."

"But what I'm saying is the government is making ways so that PWDs will be included the next time aid is given. And the LGUs are making ways for their budgets to include PWDs and senior citizens," he says in Filipino.

RELATED: Lapid bill seeks monthly social pension for PWDs

He added that the complaints from PWDs are few and far between. "Those who complain are very few... In our personal opinion more are served than those who complain."

In the meantime, the lives of those left unserved remain on the line, either by their existing ailments, or by COVID-19, to which they are effectively rendered more vulnerable.

Mendoza says the problem is worse than it seems. “In the Philippines, 90% of the PWD sector did not get aid.”

“I’m not kawawa, ha? I just drink this life-saving tablet I buy off my disability fund that I’ve worked for for how many years, but I get by,” Jose says.

- Latest

- Trending