Typhoon-proof village waits to be replicated

NADI – When Tropical Cyclone Wilson, the most powerful storm to hit the Southern Hemisphere in a century, roared across the South Pacific at 320 kilometers per hour in February 2016, it flattened much of the island state of Fiji, like Super Typhoon Yolanda did in Eastern Visayas.

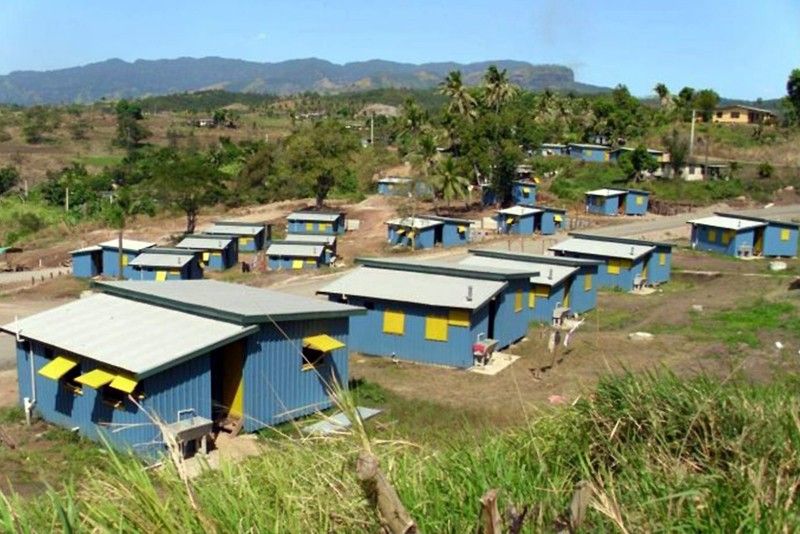

Left standing were hundreds of shelters that look like huts, nestled in the lush hills three kilometers from the city of Lautoka.

They may look flimsy, but the single-story shelters, as Wilson showed, can be described as cyclone-proof.

And they are part of a self-sustaining community for some of Fiji’s poorest who are most vulnerable to natural disasters. The community also shelters battered and abandoned women, with court orders preventing the entry of the men who abused them.

The houses were developed by Peter Drysdale, who was transported from his native Victoria in Australia to Fiji by his parents in 1936 when he was just five. He describes the houses as “failsafe” against cyclones.

Drysdale, a graduate of forestry who at age 70 still works 80 hours a week, is considering invitations to transport the concept of his 34-year-old model town to other countries. A male visitor, he said, urged him last Thursday to do this for the Philippines.

The Koroipita Model Town, which is supported by aid from the New Zealand and Fiji governments, ranks perfect or near-perfect scores in the key sustainable development goals set by the United Nations.

Each house, which sits on a 350-square-meter lot to allow for vegetable and flower patches, has two rooms, with a separate section for the kitchen, toilet and shower. The house is made of rough-sewn timber on a concrete base, held together and reinforced with 210 lineal meters of steel strapping, 29 kilos of galvanized 100 mm jolt nails and 14 kilos of 50 mm clout nails. Each house is built to blend with the hillside environment.

Drought-free

In this scorching summer, when Fiji must contend with drought, Koroipita (literally, Peter’s Village) is drought-proof, thanks to a recycling system that treats wastewater (from the kitchens) for bathing, and black water (from sewage and effluent) for irrigation and similar purposes. Solar panels produce pure water from natural precipitation, for drinking.

All wastewater goes to grease traps while sewage is gravity-directed to septic tanks and distribution boxes, toward underground perforated pipes in an effluent field, from where the clean water is redistributed for irrigation. Lining the rolling road network are drains that have never overflowed even in the worst cyclones or typhoons, Drysdale told foreign visitors last Friday. Solid waste is used for composting.

The street lamps are solar-powered. Apart from the year-round lush greenery, 1.8 kilometers of concrete retaining walls prevent soil erosion.

Drysdale had just joined the Rotary Club of Lautoka when cyclones Eric and Nigel devastated parts of Fiji’s main island of Viti Levu in March 1985, rendering thousands homeless in the town.

With the help of the Rotary, he set up the Fiji Rotahomes Project for the evacuees. In 2002, he began targeting the squatters living around Lautoka.

He found a village lot, which he leased for 99 years, for F$15,000 a year (about P360,600 at current rates). Koroipita opened in 2008 with an initial 81 houses and six communal buildings including a kindergarten, computer school, library, a shop and office. In 2009, Drysdale registered the Model Towns Charitable Trust, where the beneficiaries’ rent of F$9 a week (about P217) per household goes.

Volunteers

In 2011, with help from the New Zealand Aid Program, Rotary International, the Fiji government and other donors, stage two of the project began. The European Union also contributed to the project.

Koroipita currently has 241 homes for 1,100 people, built at a cost of about $11,500 for the materials alone, or a total of $28,300 including land acquisition, cost of labor and other miscellaneous expenses. Over 34 years, the project has built 979 houses for 4,409 people.

The Fiji government has committed assistance for the next stage, to add 145 more homes for 1,740 people. Drysdale hopes to increase the community to 1,124 houses by 2024 – 386 in Koroipita itself, and the rest in neighboring hillside areas, with a population of 1,750 people.

Last Saturday, Fiji’s head of government, Aiyaz Sayed-Kahiyum, said at the closing of the Asian Development Bank’s annual Board of Governors meeting here that they were looking for more funding to finance the expansion of the project.

He said the Fiji government connected Koroipita last year to the main electricity grid in Nadi.

Some 1,920 foreign volunteers, mostly from Australia-Tasmania, New Zealand, Britain and the United States, have helped build Koroipita.

In 2013, with help from the Habitat for Humanity and other volunteers, Drysdale and his team were able to complete 22 houses in 15 working days – a speed that he stresses is crucial during a natural disaster.

Move forward, upward

Drysdale has developed what he describes as a holistic community development program that can be compared to a conditional assistance program for the very poor.

Residents must sign an “occupation license” committing to abide by rules such as keeping children in school, and must demonstrate progress on a “family advancement plan” through education and learning of livelihood skills.

Violators of the agreement can be evicted. In the past six years, 40 families have been evicted for violations.

The community is run by a council composed of 18 block leaders, 16 of them currently women.

Residents, Drysdale said, “must move forward and move up.” Once parents have acquired the needed skills to earn a decent living, they are sent back to the mainstream Fiji community.

There are no second-generation residents. Several graduates of the Koroipita school have topped their classes in higher grades upon moving out to other parts of Fiji.

Garden of Eden

All 650 students from the community “have moved outward and upward to tertiary education, good jobs, good marriages,” Drysdale said. “This is a university of life.”

He is proud to say that the “garden of Eden” has zero school dropout rate as well as zero cases of dengue, scabies, leptospirosis and meningococcal diseases, which are problems elsewhere in Fiji. The immunization rate is 100 percent.

“Koroipita is the first of what could potentially be a series of model communities in Fiji to address the problems of squatter settlements in peri-urban areas, manage urban drift and accommodate and assimilate climate change refugees,” Drysdale said.

There are 102 micro enterprises operating in Koroipita, producing handicraft, sweets and other food products. About 80 of the operators are women.

Residents are assisted in guiding basic documentation from the government, such as birth certificates, tax identification certificates, passports and voter registration, and how to obtain basic services such as public health care and assistance in searching for jobs.

There are currently 1,700 families or 7,650 people applying to be part of the community.

“We need to scale up, replicate, build more of these,” Drysdale told visitors.

- Latest

- Trending