YearEnder: From RH to Dengvaxia, DOH copes with controversy

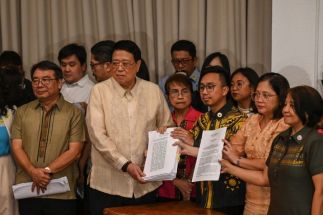

A health worker shows unused packs of anti-dengue vaccine Dengvaxia before returning it inside a freezer at the Manila Central Vaccine storage in Sta. Cruz, Manila on Dec. 5, 2017.

MANILA, Philippines — The Department of Health (DOH) started 2017 on a bright note, with President Duterte signing in January Executive Order No. 12 in support of the implementation of Republic Act 10354 or the Responsible Parenthood and Reproductive Health Act of 2012.

Before the year ended, however, controversy marred the DOH’s P3.5-billion anti-dengue immunization program that allegedly exposed thousands of children in public schools to health risks after being vaccinated with Dengvaxia.

Health Secretary Francisco Duque III said the Dengvaxia mess was the biggest scandal faced by the agency in 2017.

“It’s a continuing struggle to put things in perspective because the issues are very complex and the public hardly understands what Dengvaxia is,” Duque, on his second tour of duty at DOH, told The STAR.

Last October, President Duterte named Duque as health chief, a post he held for five years from June 2005 to January 2010 under then president Gloria Macapagal-Arroyo.

Duque replaced former health secretary Paulyn Ubial whose appointment was rejected by the Commission on Appointments.

On Nov. 29, Dengvaxia manufacturer France-based Sanofi Pasteur shocked not only the Philippines but the world when it announced the results of its up to six years clinical trial that the vaccine “provides better protection for those who were previously infected with the dengue virus.”

The analysis found that the vaccine could prevent severe dengue for at least 30 months. In the longer term, severe cases may occur following a subsequent dengue infection among those not previously infected.

At least 830,000 students in public schools in the National Capital Region, Region 3 and Calabarzon as well as selected areas in Cebu received dengue vaccines. The number does not include those vaccinated in private clinics.

Duque said the controversy cast doubt on the entire immunization program of the DOH, which covers other vaccine-preventable diseases.

“You submit your children to vaccination because you don’t want them to get sick. But after the Dengvaxia issue, parents may be afraid of having their children vaccinated,” he said.

Duque admitted that because of the Dengvaxia scandal, they may have to re-introduce the government’s immunization program to the public.

“It will be like we are starting all over again. We have to come up with a more credible information and communication campaign to regain the trust of the people about our immunization programs,” he said.

The health chief said other “success stories” of the DOH should not be overshadowed by the Dengvaxia controversy.

Tetanus elimination

Duque said this year, the Philippines became the 44th country in the world to eliminate maternal and neonatal tetanus, as determined by the World Health Organization and United Nations Children’s Fund.

He said the country was able to achieve less than one neonatal tetanus case per 1,000 live births per province or city.

Reproductive health

The DOH scored another victory when Duterte signed EO 12 in January based on the proposals of the agency during Ubial’s watch.

Ubial, who headed the DOH from July 2016 to October this year, said the EO would ensure that the Reproductive Health (RH) Law would be implemented to increase women’s access to modern family planning methods.

The biggest stumbling block to the RH law was removed when the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) re-certified late last year that contraceptive products in the market are safe and non-abortifacient.

The move led to the lifting of the temporary restraining order (TRO) issued by the Supreme Court on the renewal of licenses for the contraceptive products by the FDA.

The TRO also prohibited the DOH from including subdermal contraceptives Implanon and Implanon Nxt in its family planning programs.

When the TRO was not yet lifted, there was growing fear among family planning advocates that the country would be running out of contraceptives by mid-2018.

Around 500,000 unwanted pregnancies and 1,000 maternal deaths occurred since the TRO took effect in 2015.

Smoking, firecracker bans

The DOH’s campaign against cigarette smoking also gained ground in May when Duterte signed EO 26 imposing a smoking ban in public places.

The EO contained the revised proposals of the DOH to prohibit smoking in enclosed public places and conveyances such as schools, universities and colleges; playgrounds; restaurants and food preparation areas; sports complexes; stairwells; fire hazard places like gas stations; health centers; clinics; and private and public health facilities; hotels; malls; elevators and public transportation.

In 2017 the DOH achieved one of its goals – to limit the use of firecrackers during New Year revelries after the President signed EO 28 banning the household use of firecrackers.

Duque said it is about time that Filipinos welcome the New Year using other noise-making devices.

“Be safe during the holidays. I encourage everyone to join community fireworks display in the barangays. Do not compromise your health and welfare by using firecrackers,” he said.

The use of fireworks and other pyrotechnic devices should be confined to communities to minimize possible injuries and casualties.

Every year, a majority of firecracker-related injuries being documented by DOH involves children who use piccolo, an illegal firecracker.

Four boys, aged 11 months to 12 years old, sustained injuries from firecracker blasts as of Dec. 23.

Bird flu

The Philippines recorded its first avian flu outbreak in August in a farm in the municipality of San Luis in Pampanga City.

After two weeks, the bird flu outbreak spread to the towns of Jaen and San Isidro in Nueva Ecija.

Hundreds of thousands of chickens, quails and ducks in the affected farms were culled by the Department of Agriculture. Farm workers were placed under strict monitoring to contain the outbreaks.

There has been no case of human transmission.

Prior to the outbreak, the Philippines was free from bird flu for 20 years.

- Latest

- Trending