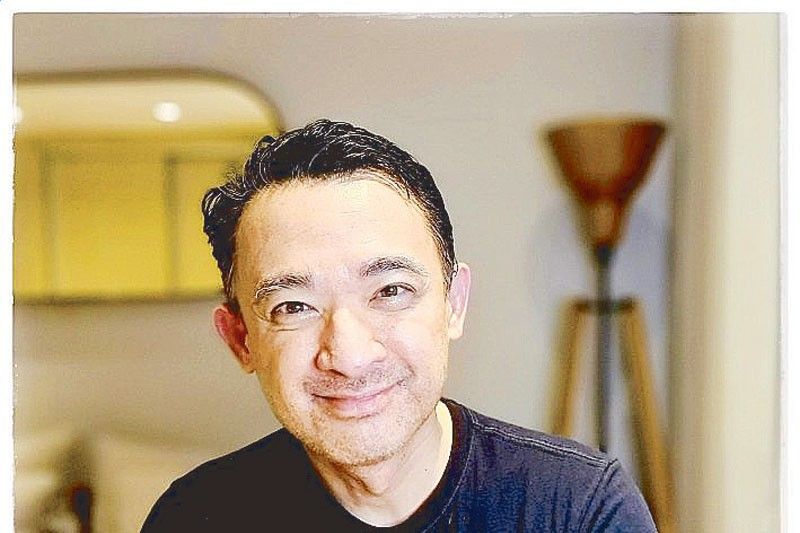

What ‘pride’ means to my friend, Randy Razzle Daza

Because June is Gay Pride month, I’m sharing a piece written by my dear friend, Randy Estrellado, who is the chief operating officer of Maynilad Services. Prior to that, he was the chief finance officer of ABS-CBN Corporation from 2000 to 2006.

I met Randy in the summer of 1998 during the Management Conference of ABS-CBN in Subic Bay. We were introduced by Jorge Lichauco, who suddenly had to leave for Manila and asked me to take care of Randy, his officemate in Benpres. After Jorge unceremoniously left Randy with me while I was grocery shopping in Royal Subic, Randy graciously pushed my cart the whole time I shopped. Little did I know he was going to be AVP for Treasury and Investor Relations of ABS-CBN in December 1998, and by 2000, its chief financial officer. Since then, Randy and I have kept in touch and we see each other regularly, especially during his birthday celebrations.

I’ve asked Randy’s permission to publish his story, from mydeepfriedtruth.com, to celebrate Pride month, and he gladly obliged in the hope that straight fathers who read his story will not alienate their LGBT children.

Kulang sa yabang or what pride means to me

When I was already the CFO of a publicly listed company, my boss called me to his office for a rare chat about my performance, and how he thought I could do better. I came with my pen and notebook prepared to take notes, but not to hear what he had to say: “Kulang ka sa yabang!” — “You are not arrogant enough.”

On one hand, as I would later tell my friends at work about the conversation, I thought it was another example of an unactionable advice from my CEO, whom we would sometimes describe behind his back as someone out of touch with the common Filipino. After all, didn’t our culture look down on arrogance and prefer the humility of the quiet worker?

On the other hand, I did not talk to anyone about it because I knew exactly what he meant. Years of being a gay man living in the proverbial closet had taught me, perhaps too well, the art of being nice — harmless if not invisible. And that was not what he wanted from his CFO. He wanted someone more confrontational. Someone who welcomed conflict rather than avoided it. In his words, “may yabang.”

In my mind, I rationalized that I was not that kind of person. That I was a part of the new generation that understood that we did not have to fight tooth and nail to find solutions to our problems. That we can always find common ground. But deep inside, I knew that part of my desire to avoid conflict stemmed from the fear of a fight getting personal and getting called the dreaded word, bakla.

Haters gonna hate

“Bakla.” B-A-K-L-A. Five letters. Two syllables. But in Filipino, it covers a multitude of meanings from the scientific but dry “homosexual” to the more everyday and friendlier “gay”; from “bi” which only gets it partly right, to “trans” which doesn’t get it at all; and to how we all grew up hearing it being used — the pejorative “faggot.”

In 1994, there was that indie rock song Multong Bakla that somehow equated being gay to being a scary ghoul, a disgusting fly, a spread-eagled cockroach and a plague to society, among others. And yes, it was a big hit that got massive airplay and brought the band that sang it to the mainstream. The song ends with the whole band joining the lead singer shouting, “Bakla!” and there was no doubt as to which of the word’s multitude of meanings they meant.

Hearing this song on the radio 26 years ago gave me no doubt as to what a gay man’s place was in Philippine society, let alone the corporate world. As most gay men of my era did, I kept quiet, gave an enigmatic smile, and played nice whenever I was asked why I didn’t have a girlfriend or why I wasn’t married. I was 29 years old and already a manager. But as a single man, it was not yet clear that there was room at the executive lounge for a bakla like me.

Why you gotta be so mean

It seems like I should remember it better, but I barely recall the first time I heard the word “bakla.” It must have been in a fight with a neighborhood kid just a year older than me when I was around four years old. A disagreement that ended with me taking back my toy and with him responding with that word. While I did not know what it meant, I understood even back then that it was meant to hurt.

Growing up was a series of lessons on managing that hurt. I don’t remember going home after the fight to ask my parents what bakla meant. Turns out, I didn’t need to because over time, I would hear it often enough to know it was not something anyone would want to be. Definitely not in my father’s eyes.

“Huwag ka ngang ba-bakla-bakla.” I cannot count the number of times I heard my father say these words. He was a good person, a handsome and charming man admired by many. But like many a military man of his generation, he considered bakla the worst thing you could say about anyone.

I loved my father but I grew up afraid of him. “Para kang bakla,” he would say. So around him I was always on my guard. He thought I was too soft. At times too proper. I recall Christmas gifts that I didn’t ask for and pretended to like — toy guns and boxing gloves — apparently intended to toughen me up.

On a road trip to his home province, I heard him complain to my mother that like a bakla, I talked too much. I fought back tears and pretended to nod off in the car, doubly hurt as I was only making conversation so he wouldn’t fall asleep on the long drive home. Pretty soon, I learned to stop the tears from falling even without closing my eyes.

Sticks and stones

I know my father meant well, and whether what he did was bullying or not, it did give me the skills to cope with bullying, mostly by learning how to avoid it in the first place. At home, that meant trying to reduce interacting with him, burying myself in books, and sometimes even feigning sickness to get away from attending events with the family.

These techniques were harder to apply in school. I was and still am a lousy athlete who can’t dribble a ball to save my life, so I dreaded P.E. classes the most. It was 60 minutes of torture for me but it was also 60 minutes of forced interaction with possible bullies who taught me how to react to them — I just didn’t.

Apparently, bullies don’t enjoy it when you don’t allow them to get to you. Or if you’re able to laugh it away. Eventually, I learned to read bullies and calibrate the appropriate response. Fortunately, I also did not have the body type that drew bullies in — neither too fat nor too thin, neither too short nor too tall. And because my father had drilled out my more effeminate traits, there was nothing to target.

All this avoidance did not come without a cost. I do not have close friends from my childhood or from the neighborhood I grew up in. And while I eventually became a person my father could be proud of, he did not know what I went through to get there — the fears and insecurities I overcame, the risks and sacrifices I took. We did not have that kind of relationship. Years of hiding did that and he unfortunately passed away before I had the courage to let him know the real me.

Let your colors burst

I know it’s an imperfect world and that it’s sometimes hard to see if we’re changing for the better. But only 17 years after the song Multong Bakla played on the radio, the straight rapper Gloc-9 came out with Sirena, a song sympathetic to the gay struggle for dignity. “Kahit anong gawin nila, bandera ko’y di tutumba (No matter what they do, my flag will keep on flying).”

I no longer have the same boss, and I have been out at work for the last seven years. I’m not sure it has made me actively seek out conflict, but I’m sure it is no longer something I am afraid of. I don’t necessarily encourage conflict, but knowing the pitfalls of avoiding unpleasant conversation, I make sure the environment is open and safe to express one’s views.

“Bakla ako! — “I’m gay.” After decades of fearing it, I no longer flinch when I hear the word bakla. I know it carries the stigma of generations but what can I do other than own it when it’s the only Filipino word for it? Unless we use gay lingo, which is another story.

(On a side note, I object to gay men putting down people they don’t like, particularly politicians they disagree with, by calling them bakla. I think it’s internalized homophobia, though my friends whom I’ve called out for doing it insist that it’s just for fun.)

I’m not a political person and I have yet to walk at a Pride March. My work and the difficulty of separating my personal and professional personas prevent me from taking a more public role. But I am grateful to everyone before me — in the Philippines and around the world — who has allowed me and other LGBTQ individuals to be the persons we can be today.

And so, I celebrate Gay Pride and make sure I am counted. Discriminating against anyone deprives us of the fullness and beauty of human life. Lives and relationships we cannot recover and should not be able to afford to lose. We are all worthy people of every color of the rainbow.

- Latest

- Trending