The Joker is wild

Film review: Joker

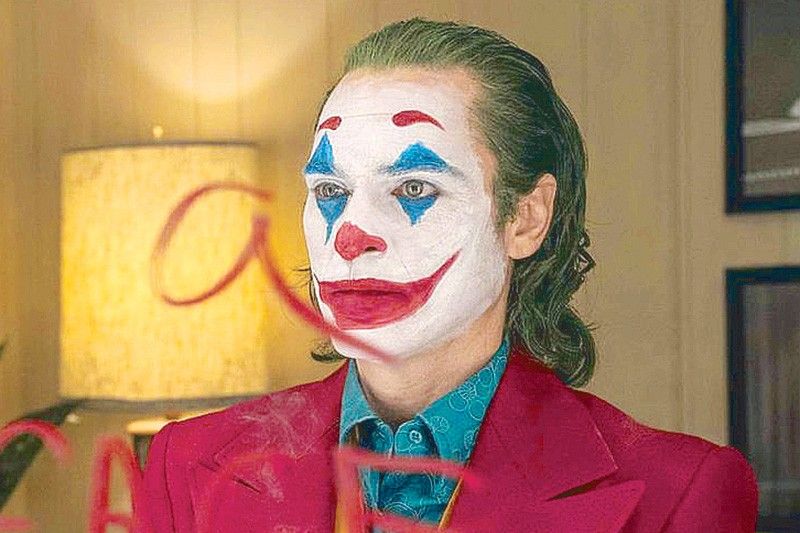

MANILA, Philippines – In Todd Phillips’ Joker, Gotham City is filthy, fierce and forbidding. It is in this environment where lives Arthur Fleck (Joaquin Phoenix), who will eventually become The Joker. Dysfunctional and deranged, he has a neurological condition that makes him laugh uncontrollably at times. In addition, he is broke, malnourished and lives in squalor with his sick mother (Frances Conroy).

The movie starts with a bang, literally, with Arthur bullied and then beaten up by young thugs. Taking dubious pity on him, his fellow clown Randall (Glenn Fleshler) sells him a gun for self-defense. But Arthur gets fired (no pun intended) for bringing the gun to a children’s party. Dejected, he takes the subway home, only to be beaten up (again!) by three arrogant yuppies annoyed at his incessant laughter. These he promptly dispatches one by one. The killings become a cause celebre among the many in the Gotham hoi polloi and Arthur (anonymously as the “Killer Clown”) attains cult following.

Trying his hand at stand-up comedy to support himself and his mother, Arthur fails spectacularly. But he gets the attention of a member of the audience, who films his embarrassment and sends it to the Murray Franklin Show, a talk show that is his and his mother’s favorite.

Asked to be a guest, he shows up in full clown regalia, leading to a verbal tiff with the host (Robert de Niro) that ends in tragedy, and to the film’s high point. In between, there is gore galore as Arthur goes on a killing spree to cover up his authorship of the first murders.

Phillips makes no bones about his admiration of legendary director Martin Scorsese (Taxi Driver, 1976; Raging Bull, 1980; Goodfellas, 1990), whose dark films are the gold standard of character study noir. Thus, the pervasive homage to Scorsese’s film style: Slow motions, long takes, chiaroscuro and that “you talking to me” scene in Taxi Driver. This results to a movie that is visually gorgeous and compellingly dynamic. Optically, Phillips has almost gotten his idol’s look down pat.

Unfortunately, the similarity ends there. Joker glaringly lacks the essence of a Scorsese film — or any good character-focused film in general — and that is a profound study of the protagonist. In Taxi Driver, the personality of the lead is shown to the viewer over time through his interaction with other players: De Niro as to Jodie Foster’s child prostitute, Cybil Shepherd’s Betsy, and Harvey Keitel’s Sport until the final reveal. In Joker, Phoenix’s Arthur mainly plays off Frances as his mother Penny, she with a history of mental disease. I had initially thought Zazie Beetz, as Sophie, would be the film’s Foster, the one who would bring it to a violent catharsis, but then it would later be shown that their “relationship” was but part of his many delusions. The exposition of Arthur’s character thus comes off as shallow and half-baked.

To provide motivation for all the violence, much capital is made of the fact that the Joker is mentally ill, as if to say that he is not responsible for his malevolent acts. It would have worked if the gore was exhibited for more than shock factor, as Stanley Kubrick did in A Clockwork Orange (1971) as a preface to his commentary on society, delinquency and criminal reformation. Joker’s carnage has no such transcendental aim. It shows Arthur killing people merely because he is criminally insane. Worse, in the absence of considered compulsions, the movie justifies ordinary people’s acts of violence as due to society’s indifference: The rich look down on the poor as “clowns,” government does not care for the common folk, and thus the underprivileged must struggle amongst themselves for survival.

To be sure, Phoenix, De Niro and the rest of the cast act excellently. And if explicit brutality is your kind of entertainment, Joker will deliver. Phoenix especially takes on an exaggerated persona to accentuate the Joker’s absolute unscrupulousness. “I have no beliefs,” he declares towards the movie’s ending. In the face of the film’s none too subtle pontificating on societal ills, however, such disclaimer rings untrue. Suffused with platitudes, Joker is a film set in the early ‘80s that tries to be relevant to today’s world view. The “punchline” falls flat though, notwithstanding Phoenix’s powerful internalization of his role, which includes wild balletic pirouetting at times. Thus, in the end, you leave the theater bereft of any substantial message, feeling, like Shakespeare must have, when he wrote that life is “a tale told by an idiot; full of sound and fury, signifying nothing.”

- Latest

- Trending