Looking for Rizal, the environmentalist

MANILA, Philippines — Barely a month before this year’s Rizal Day, the hardcover “Rizal+” was launched at the RCBC Plaza in Makati, the book a compendium of essays on the national hero written by various authors. Edited by Krip Yuson and in long format edition that recalls the size of the magazine Ermita in the martial law era ‘70s also edited by him, Rizal+ serves as a reunion of sorts of that counterculture rag, as both were published by Boy Yuchengco of Water Dragon Inc. and includes writers Cesar Ruiz Aquino, Sylvia Mayuga, Jose Victor Peñaranda – all in the staff box of Ermita.

Now where does Jose Rizal as environmentalist fit in all of this? As school kids we learned of the hero’s conscientiousness if not awareness of his surroundings, including a slew of anecdotes, some possibly apocryphal that date back to his own childhood years – how he was virtually entranced by his mother’s tale of the moth and the flame, a throwback to Icarus if not Melville’s Moby Dick and Ahab’s warning not to “stare too long into the fire, young man”; his throwing one remaining slipper into the river or bay after the first accidentally fell into the water, a kind of self-styled sustainability; and after winning the lottery while in exile in Dapitan, investing in agricultural land and teaching the natives the mechanics of irrigation and setting up the first electric lampposts in town.

The essays in Rizal+ inevitably add to what we learned of Rizal in elementary school days, mostly from Camilo Osias’ Philippine Readers, supplement it with a kind of metaphysical or metafictional knowledge of the hero, as it were, through astute scholarship and a doggedness to chase the image or idea to the depths.

Aquino, for instance, makes much of the blind stepfather of Josephine Bracken, Taufer, who in the inordinate dark must have been unconsciously groping for the muse, the writer using as objective correlative or outright peg of his metacritique a poem by Wilfredo Sanchez based on Rizal and Josephine, “Love in Talisay.” He points out that Rizal was born in the summer solstice and died in the winter solstice, which is described by Thomas Mann as “when the sun is its own ghost.”

Mayuga writes a letter to Lolo Pepe, her sentences ringing with a cadence of “Love never gives up on Avenida.” Decades removed from the blind beggar of Rizal Avenue she and a team of ornithologists revisit the foothills of mystic Mt. Banahaw, base of Tres Personas Solo Dios, and find rare birds and a flying bat never seen before.

Peñaranda, whose death last year saddened the literary community, traces Rizal’s freemason roots and how the secret society was instrumental in the revolution that overthrew Spain. Well researched to the point of artlessness, his essay revisits the choices presented to Rizal en route to Bagongbayan, including names of the ships the hero boarded or was detained: Espana, Castilla, SS Colon.

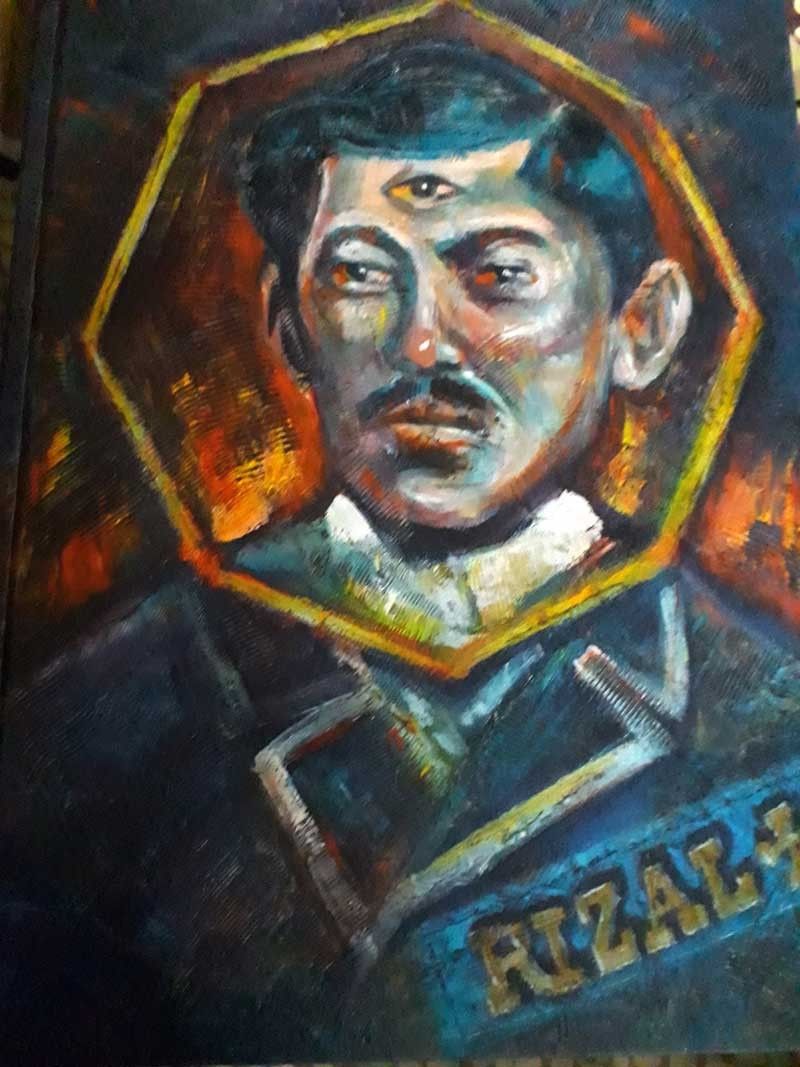

It was at Peñaranda’s instigation that the Rizal+ project got started for the national hero’s sesquicentennial in 2011, but was shelved by a series of events. The main artist, Edd Aragon, who did numerous portraits and studies of Rizal including the book cover, has also passed on.

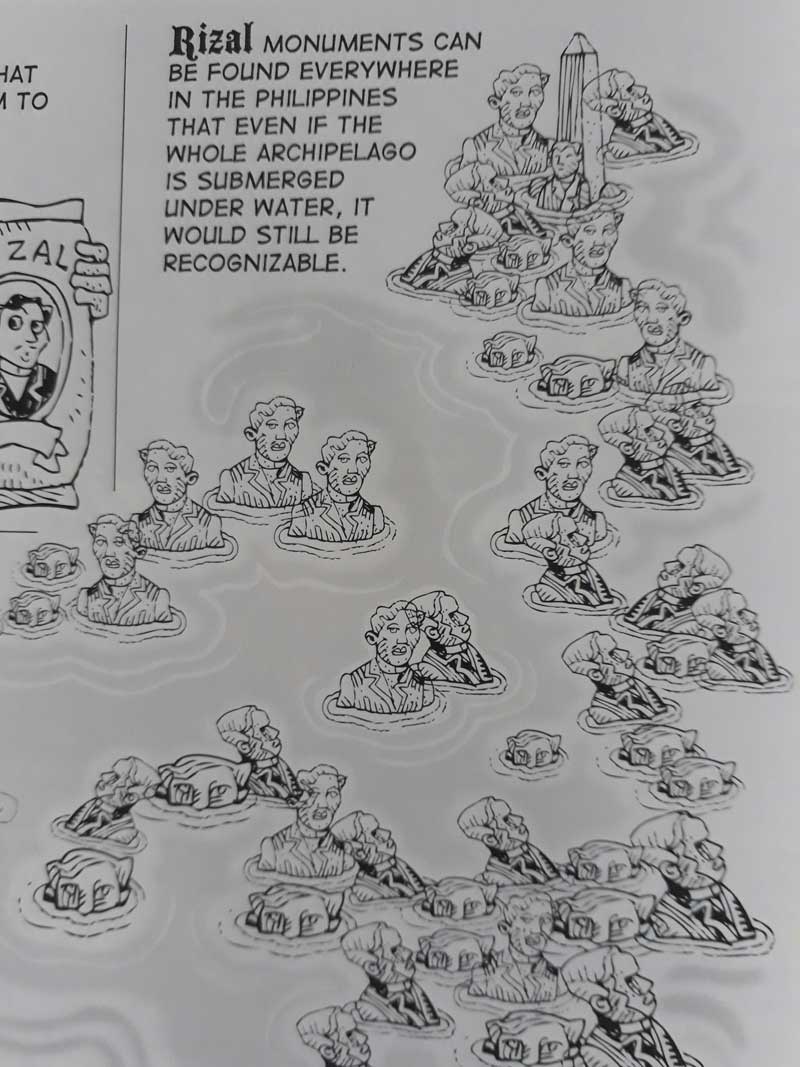

But Aragon is ably assisted in the visuals by Dengcoy Miel, whose comics panel on the postmodern Rizal is a welcome change of pace. Other fine writers also contributed: Butch Dalisay with the hero on a world poker tour, Jose Lacaba with an excerpt from a film script and ruminations on the alleged gayness of the subject long before the word changed meaning, Erwin Castillo on gunmanship and Rizal’s affair with the Smith & Wesson, and the aforementioned Sanchez in a letter to Sawi (Aquino), saying: “I remember, many years back, Erwin and I chatting about what aspect of JR we might want to render fictionally. I told him I’d place JR against the backdrop of Aden or Montjuich and he said he’d stick him in an elevator in Chicago with the first black guy he ever encountered.”

There are some omissions of course, but what far-ranging project doesn’t? Greg Brillantes’ “Looking for Jose Rizal in Madrid” is nowhere to be found probably because sui generis, while Cesar Hernando’s take on Rizal in film fails to cite Mario O’Hara’s late ‘90s “Sisa.”

Let’s leave it to Yuson, who in his speculative meta-review quotes Aquino de Dumaguete: “In his mind’s eye, the genius who would turn martyr recalls all those months he had worked with schoolchildren on the project. He had taught them how to shape the wet clay and pat the material into place, then smoothen the ridges of Mt. Apo or scoop out the hollow that would be Lake Lanao. Oh how the mud, as the boys called it, felt in their hands. When he himself was yet their age, he had shaped figures: a dog, a crocodile, a naked lady holding a torch and standing triumphant over a skull.” (Reimagining Rizaldry: A review of Rizal’s Lizard) – JYA

- Latest