A year after, Filipinos are now asked to go out; the youth don't want to

MANILA, Philippines — Months after the Philippines dismantled its tough lockdowns late last year, three friends invited Emelyn Rivera to dine out. Curfews were still in effect, but establishments were nonetheless open so long as strict health protocols were observed.

But she did not go. She wouldn't go out now either.

That was even after her friends volunteered to pick her up and drive her home after, a go-around to reduced public transport as well as to limit contact and avoid contracting the coronavirus. “I always tell them I don’t want to go because I’m still afraid to go out,” she said in an interview just outside her home.

In September last year, the building where Rivera's former office as marketing officer was based reported its first case of coronavirus. The infection was not even in her office per se, but that it was close enough was valid reason to resign even amid the hard times. Now, she earns far less from selling homemade food items, but the relief knowing that you are not bringing the virus home to your parents with comorbidities is priceless.

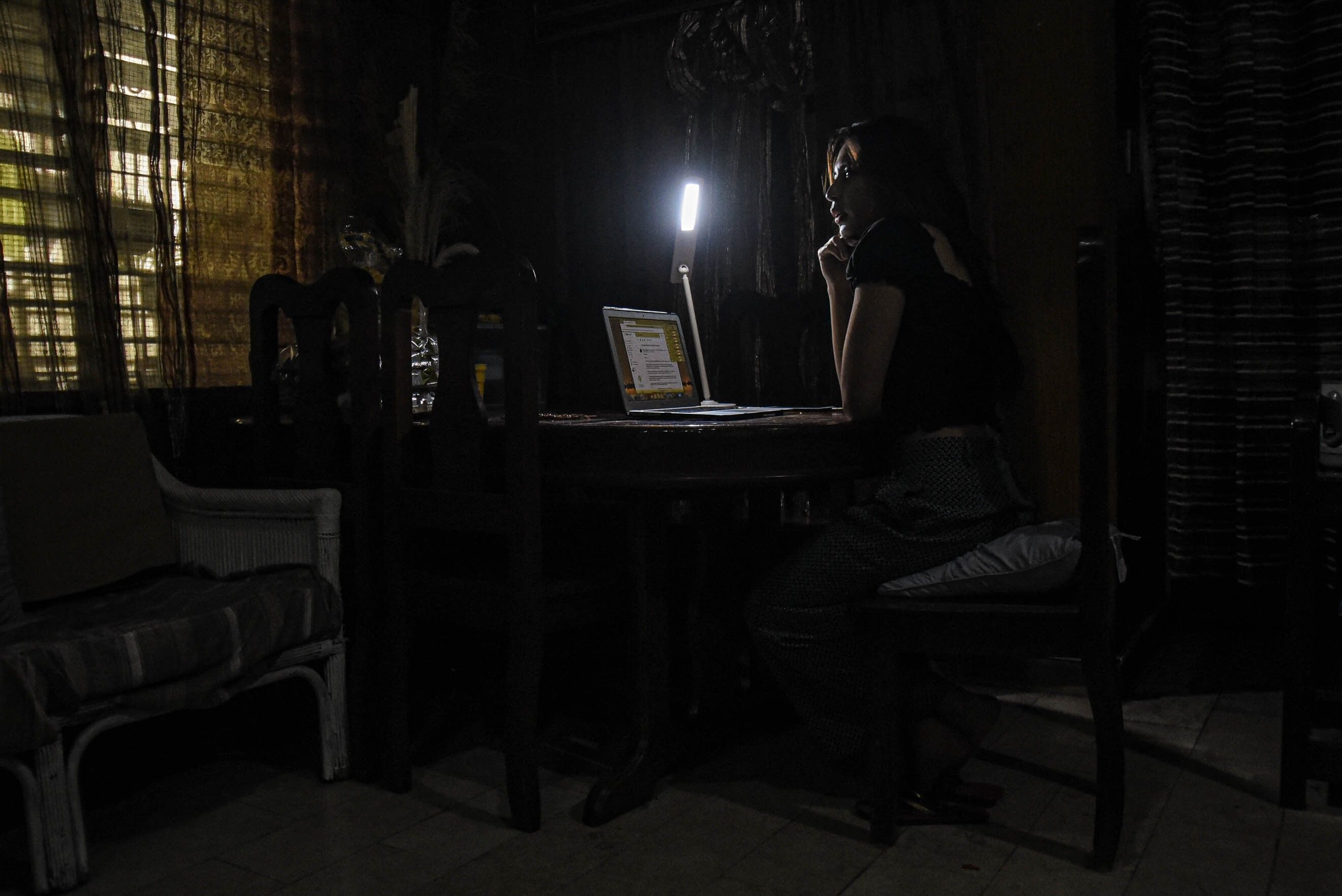

Other family members were also put on notice. In normal times, Rivera would travel to La Union for the New Year. During recent holidays, the deadly virus instead forced them to stay indoors, facing a monitor as a Zoom call with their relatives kicked off what was typically a big family gathering.

That was January 1. With the end of first quarter fast approaching, Rivera remains part of now wary legion of young Filipino consumers choosing to stay home, and anxious of catching the deadly disease if and when they step out. It was a behavioral change warranted at the start of pandemic, but which the government is now having difficulty reversing when they need them to spend the most.

“For me, it’s scarier to go out this time that cases are higher. There’s a higher possibility that we get exposed to a bigger crowd, and that’s alarming,” Rivera said in Filipino.

“I still feel anxious that, unknowingly, I may have contracted the virus while doing important errands and bring it home,” said Rivera who lives with her parents and a cousin. “It’s hard to be complacent at this time.”

There is one sensible reason why this anxiety has to be relieved. With the anniversary of the health crisis, the government has realized the enormous cost of lockdowns on the economy, much more when 70% of annual economic output is coming out of the pockets of the likes of Rivera, 25.

The change in government pandemic messaging is obvious. On Harry Roque’s podium during press briefings, gone are the words “Stay Home,” now replaced by more lenient reminders of “mask, hugas (wash hands), iwas (social distancing).”

But as last in line on getting the delayed vaccines, young Filipinos whose spending is critical to economic health are not taking any chances and are choosing to patiently wait for their turn, together with their more vulnerable families. Hence, while the Duterte administration now wants consumers out there, nobody seems to be listening.

Spending changes

Not even Bettina Pangalangan, who lives a few minutes away from Rivera in Quezon City. After leaving a cushy job at the House of Representatives before the pandemic hit, she now has less reasons to go out with writing stints that enable her to work remotely.

It was a 360-degree turn that gave her more personal time: before, she could barely fit her busy routine of workouts, going out with friends, and actively participating in Church— all typical for a woman in her 20s. But the changes she witnessed during the crisis also transformed her routine and what she spends on.

From parties three times a week, and periodic vacations with friends up North, she now allots most of her budget to groceries that put food on the table for her siblings. The pandemic has nonetheless revealed new personal needs, including monthly psychiatric consultations to keep her mental health in check. “I also became a 'plantita' at some point,” she said, pertaining to a trend of keeping plants at home that came with the pandemic.

Yet even going out for essentials carries with it apprehensions about the likelihood of getting infected. When malls reopened, Pangalangan was among their usual patrons that did not immediately return. When she has no choice but to shop for essentials, each trip is planned so that she maximizes her time and does not have to go out as often. “When I go out, it’s all in one go. Salon, facial, everything that I can fit in my schedule, even groceries. Because after that, you will have to quarantine yourself again, right?”

“I don’t see malls as essentials right now,” she said.

Once home, taking a bath before anything else is a must. It is a personal safety protocol she and her brother who works as a nurse would not easily give up, knowing exactly how coronavirus tarnishes people's lives when their grandpa died of COVID-19-induced pneumonia last year. Their parents, medical workers in the US, also caught the virus, but thankfully already recovered and now vaccinated.

The Pangalangan's neighborhood itself is home to Metro Manila's highest coronavirus caseload to date, and among areas that starting Monday, reinforced curfews and checkpoints in time for the lockdown anniversary. But even without going out, their small residence, rented and sharing a verenda with other families, is something that keeps her awake at night. “It feels like ground zero here,” she said.

Last dibs

Jason Cayetano, 28, also had to accept lifestyle changes. Working for a business process outsourcing firm, there was a time when, after his shift, he and his friends would spend hours outside drinking. For a time, many thought that Friday nights like that would return as soon as curfews were lifted. They did not.

When curfews were relaxed last December in time for Christmas, establishments still closed down at 9 or 10 p.m. and roads were deserted almost instantly. “Drinking spots near the office are gone. The ones open in the morning, disappeared. I've already accepted that fact,” he said in an interview.

Many believe that the shock only altered, rather than exhausted the Filipino spending power. One argument is the digital revolution that buoyed delivery services and online shopping during the pandemic likely put many consumption activities beyond government record. But there is no denying that at some point, people would have see some normalcy restored and that not happening now is only hurting President Rodrigo Duterte's legacy.

Before the health crisis messed things up, the administration pledged to propel the Philippines to an upper-middle income economy. That has all changed, and, at the very minimum, this government just wants to restore the entire P1.5 trillion in gross domestic product losses last year before he steps down from office. It’s a goal getting more far-fetched by the day with many consumers unconvinced it is safe to be out there.

Having the last dibs on the vaccines, expectations that young people like Rivera, Pangalangan and Cayetano would be the first to give the broader economy a nudge turned out easily misplaced. After all, being last in line for vaccines yet to arrive for the the broader public does not really invite consumer confidence.

“If vaccines have been rolled out already and if we're seeing good results from it, cases are lessened each day, maybe that's the time that I'll be confident in doing the usual things that I do before the pandemic little by little,” Rivera said.

Neither does it do anything to alter the unsafe environment cultivated by an inadequate state handling of the virus a year after. And then there is also vaccine hesitancy to worry about. “I'll get vaccinated myself so long as it is Pfizer and Moderna...My Mom said never to get the Chinese brand,” Pangalangan said. — Photos by Efigenio Toledo IV and Deejay Dumlao

- Latest

- Trending