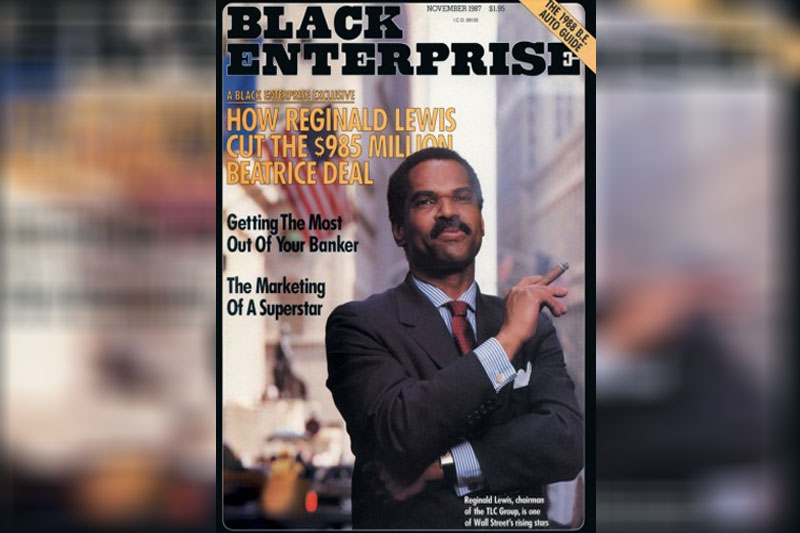

Inside Reginald Lewis’ billion-dollar acquisition of Beatrice International and how the deal transformed black business

In the November 1987 issue, BLACK ENTERPRISE reported on the groundbreaking deal in which financier par excellence Reginald F. Lewis acquired mammoth Beatrice International Foods for roughly $1 billion. As a result of that transaction, Lewis created the first black-owned conglomerate to generate more than $1 billion in annualized revenues and inspired generations of black dealmakers on Wall Street.

In the following article, Rene “Butch” Meily, former VP of Communications for TLC Beatrice International, offers a first-person insider’s account of the deal, the strategic brilliance and the hard-charging style of the late business trailblazer based on personal interviews; his upcoming memoir, Before the End; and the book Why Should White Guys Have All The Fun? by Blair Walker, soon to be released on Audible.

It was the 1980s, the decade of Ronald Reagan and deregulation, of Cyndi Lauper and Michael Jackson, of extravagance and excess, where getting rich was on everyone’s mind. New York was in a long period of decline and people were desperate to escape it. For an immigrant kid from the Philippines, I hadn’t done too badly. I’d scaled the public relations ladder, jumping from one firm to the other, until finally, I landed a job with Burson Marsteller, the “Harvard” of PR firms.

In those days, big American companies were getting taken over by people we never heard of through LBOs or leveraged buyouts. LBOs made use of “other people’s money,” money that was borrowed, to acquire a corporation using the assets of that same corporation as collateral.

Many of these LBOs were backed by one firm that the rest of Wall Street hated, Drexel, Burnham, Lambert. Its name struck fear in the hearts of every executive in corporate America, and it was led, in large part, by Michael Milken, an iconic dealmaker who made his name by fueling junk bond-financed takeovers of major corporations.

At Burson, I joined the mergers and acquisitions PR team. We were either on offense or defense in these takeover battles. It didn’t matter to us as long as they paid.

One day in July 1987, the phone rang. A woman was on the other end. She said her name was Loida Lewis and that she’d gotten my name from a Wall Street Journal reporter. She told me that her husband had a PR problem and that someone would call me.

“Don’t worry,” she said. “He’ll be a big client someday.”

I didn’t know what to make of it but I got clearance from my boss to proceed. Minutes later, the phone rang again.

“Hi, I’m Everett Grant. I work for Mr. Reginald Lewis.”

“Who?’

“Mr. Reginald Lewis, CEO of TLC Group.”

“What’s that?”

“We do LBOs, you know leveraged buyouts,” Grant answered. I’d never heard of TLC Group and there were no Google searches back then. He then proceeded to interview me, after which he finally put me through to the man himself.

“Hi, I’m Reg Lewis,” a deep voice came on the phone.

“Oh hi, Mr. Lewis.”

“Call me Reg.”

And that’s how I came into contact with the most remarkable person I’ve ever met.

Reg told me his problem. He’d recently sold an old-line home sewing pattern company, McCall Pattern, but in The New York Times article about the sale, the current managers never acknowledged the work he’d done turning the company around and even disparaged him. So, Reg being the kind of guy he was, looked up the reporter’s number in the phone book which was something you could do in those days and woke him up at 6 a.m. to yell at him.

The reporter’s name was Dan Cuff and I happened to know him. Accordingly, I reassured him, “Don’t worry Reg, I know the guy. I’ll set up an interview for you and we’ll get your version of McCall out.”

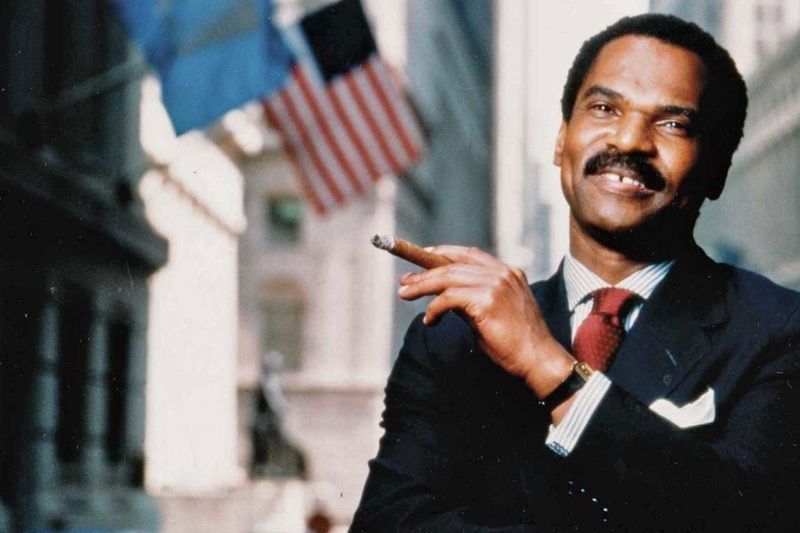

I convinced Cuff to interview Reg for a story that would highlight his contribution to the company. The next afternoon, I was waiting patiently in the lobby of The New York Times when a husky man with a mustache and close-cropped dark hair strode in through the revolving doors. He conveyed a sense of presence and purposefulness. He was good looking in a rough sort of way. But what drew your attention to him was an intensity, a drive, a feeling of caged energy ready to spring at you.

It wasn’t until he walked through those doors that I realized he was black. I was surprised because in those days, there weren’t too many African Americans in the business world. It wasn’t until much later that I learned about the demons that burned in him and gave him that drive.

He looked me in the eye, reached out his hand and said, “Hi, you must be Butch. I’m Reg Lewis.” After a quick briefing, we hopped on the elevator.

As we exited the Times, Reg offered me a ride in his chauffeur-driven blue Bentley. Once inside, he asked me how I thought the interview went. I told him I thought it went well but that triggered a harangue of angry words and denunciations. I finally asked if I could get out and walk. I had just seen the real Reg Lewis, not the smiling guy who I’d gone up in the elevator with just a short time ago. I staggered out of the car and onto the city streets. I had just met this guy and already he was yelling at me.

Three nights later, I trudged through the streets of Manhattan looking for a newsstand. Back then, you could get a copy of the next day’s paper if you stayed out late enough. I couldn’t go to bed without catching a glimpse of the story and its contents.

Reg had been painfully precise about what he wanted—the message was a 90-to-1 return for his investors, no mention about his being African American, just a photo. To get all that in The New York Times would be unbelievable. But I’d been working hard with Cuff on the article.

Finally, I spied a place in Midtown that was open. I had to tell myself to calm down as I bought a copy of the paper and flipped to the business section.

There on the front page, below the fold, was a story headlined, “90- to-One Return for Investors,” and a photo of a fierce-looking, mustached black man. I could hardly believe my eyes. I had done it!

I ran to the nearest phone booth and trembling a little, dialed Reg’s home number. Loida answered but would not put me through because Reg was sleeping. I could not believe it. I’d roamed the streets of the city to get a copy of the best story I’d ever placed and my client was asleep.

“All right,” I said dejectedly. “Please tell him I called and that it’s an exceptional story.”

And it was. The Times piece turned Reg into a minor celebrity in Wall Street circles. But at that time, I had no idea what it would eventually lead to and the change and upheaval it would bring into my life.

Reg had met Milken a few times and discussed doing the McCall acquisition with him but nothing had materialized. Yet according to Loida, Milken called Reg early that morning after reading the Times story to congratulate him and invite him to Drexel’s Beverly Hills office for a meeting.

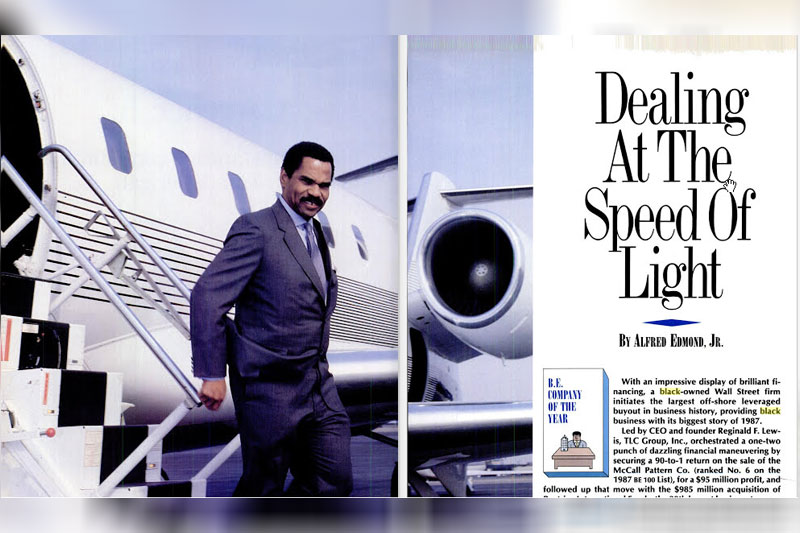

The timing was fortuitous. It happened that Reg was already working on a much bigger deal. A billion-dollar bid for one of the largest corporations in the world, Beatrice International. It had 64 operations in 31 countries.

Cleve Christophe, a long-time friend of Reg’s, had just joined TLC Group in June.

“Reg pulled me aside and asked if I would take a look at this selling memorandum,” he said. “I took it home and stayed up all night reading it.” Christophe told Reg the next day that he thought the Beatrice deal would work and came up with a computer model on exactly how to do it.

Their plan was straightforward but by no means risk-free. They had to sell off all of the Beatrice companies to repay the debt except for a core centered in Western Europe that Reg viewed as the true gems of the group. Irish potato chips, French supermarkets, ice cream companies that were market leaders in seven countries across the continent. These companies would generate enough money to give TLC a steady cash flow that could service what would still be an enormous amount of debt, even after the sale of the other companies.

The important element of a leveraged buyout is exactly that. It is highly leveraged. You only put in a small amount of actual money; most of it is borrowed and then repaid with the sale of that very company’s assets.

Reg and TLC had to structure their bid so that it was high enough to win but low enough that they could still repay most of the debt with the sale of the companies and service the rest of it with the earnings of the European core.

If they bid too low, they would lose and have to eat their enormous expenses on law firms, accountants, investment banks. If they bid too high, it could wreck the whole deal and make it impossible for them to make money on it, bankrupting the entire enterprise. In a very real way, everyone’s job was on the line.

Charles Clarkson, who Reg had hired straight out of law school and became his law partner, remembers sitting in the conference room at TLC’s sparse offices at 99 Wall Street.

“We were talking about how much we should bid for Beatrice. We made a first bid of $950 million and then increased it to $985 million. We may have been bidding against ourselves but Reg had put his whole life into the auction and if he hadn’t pulled it off, it’s hard to tell what would have happened.”

Reg himself harbored doubts which he confided to Loida. When she reassured him it would happen, he answered, “What do you know about deals?”

“I don’t know anything about them,” she countered. “But I know you. And you can do it.”

Milken was the key to the deal. Reg had to convince him that TLC Group could do the transaction.

Christophe remembers taking a call from Salomon Brothers, which was conducting the auction. The Salomon banker told him that TLC had the highest bid. “There’s only one problem,” he said. “No one knows who the hell you are.”

During the meeting with Milken, Reg took him through the Beatrice bid. According to the biography of Lewis, “Why Should White Guys Have All The Fun?,” Milken recalled that fateful discussion vividly.

“From that point on, all of our interaction convinced me that he was the right person for the transaction. … My feeling was that he knew Beatrice better than I knew Beatrice. In fact, he knew it better than the people who ran it.”

“We were viable because Milken agreed to back Reg.” Clarkson says. “Getting Drexel was big.”

After due diligence and hard negotiations, TLC secured a letter from Milken saying that he was “highly confident” Drexel could finance the bid. Henry Kravis of Kohlberg, Kravis & Roberts, which owned Beatrice, was still squeamish and during a meeting with Milken told him that although Reg had made a lot of money on McCall, he had no credibility with him in a billion-dollar deal. Mike famously responded, “Well Henry, he’s got credibility with me.”

TLC won the auction, beating out such competitors as Citicorp and BonGrain, a huge French food company. Reg called Loida with their pre-agreed code, “Raindrops keep falling on my head.”

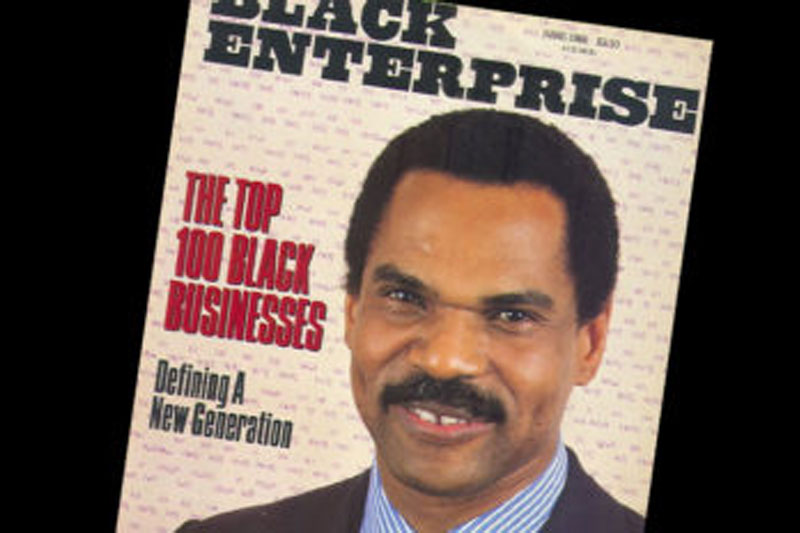

The news of TLC’s winning the Beatrice International auction swept the world like a firestorm. A black man buying a major international company was news. The name of Reginald Lewis was on everyone’s lips, particularly the African American community. He had barreled through a door and if he could do it, perhaps others could get in as well.

Milken compares Reg to the “Jackie Robinson of business” in breaking barriers and stereotypes.

Kenneth Frazier, the CEO of Merck, says, “As an exemplar of excellence and audacity, Reg Lewis opened up a world of possibilities for an entire generation of black business leaders. I distinctly recall my reaction when he engineered the acquisition of Beatrice Foods. I said to myself, “Who is this brother?’”

However, winning the Beatrice auction and closing it were two different things. Christophe recalls that it took two days of nonstop work in late November to get the transaction closed.

“It was tense,” he said. “There were people from all over the world sitting in a number of conference rooms in six floors at Paul, Weiss (which was where Reg first worked as a lawyer). There were thousands of documents to complete and sign. These were 64 companies in 31 countries with differing tax codes and earnings in multiple foreign currencies.”

There was a final bout of screaming and arguing between Drexel and Reg over the equity split in Beatrice. “Drexel was famous for coming in at the last moment and demanding a larger share of the deal,” Christophe recalls. “They had the leverage because they knew the deal wouldn’t close without them. They wanted to participate in the upside. But leverage also depends on how the cards are dealt.”

Complicating the closing was the fact that the stock market had collapsed in October 1987. In addition, Drexel was coming under intense government pressure as part of an investigation that would eventually bring it down. No transactions were getting done.

“It was us competing against the world,” Christophe says. “I could sense though that we were in a momentous part of history.” In the end, Reg won the argument. Drexel had wanted control but wound up with 26% of Beatrice. The tax issues were resolved. The deal closed on November 30, 1987.

There were casualties though. Reg’s hard-charging style wasn’t easy to take. It cost him his friendship with Christophe.

“There’d been a lot of ranting and raving,” Christophe remembers. “I think he thought there was no way I would leave with all this money on the table after the Beatrice deal. Then one day I was shaving and I looked myself in the mirror and my throat caught as I said, ‘You have to hang on to your self-respect.’”

Christophe would leave TLC by April 1988, 11 months after he joined, to embark on his own series of deals. I, on the other hand, quit Burson to work for Reg. Later, he would talk about doing even bigger deals. One of them was buying the domestic operations of Beatrice, which at the time included such household names as Tropicana orange juice, Samsonite luggage, and Orville Redenbacher popcorn. He’d discuss running for the Senate. “Once you’re in the Senate, lightning could strike,” he laughed, hinting at the U.S. presidency.

Reg would give Harvard Law School, where he had studied, the largest donation it had ever received at the time, $3 million, and had a building named after him. His foundation would give his alma mater, Virginia State University, a gift of $2 million, resulting in the Reginald F. Lewis College of Business.

He would try to take TLC Beatrice public, which would have made it the first black-owned company to be listed on the New York Stock Exchange. But the offering failed. He bought a mansion in Amagansett, Long Island. But it burned down. He became the first black man to live in the upscale part of Fifth Avenue. But in a cruel twist, he died within months of moving in on January 19, 1993, at the age of 50.

“He’s still in my heart,” Loida says. “Love never ends.”

Working for Reg Lewis wasn’t easy. He did not suffer fools lightly. But he did force everyone to raise their level of play. He challenged me but taught me as well, and not a day goes by that I don’t think of him and what might have been.

All that was ahead of us though, as we savored that moment in 1987 when we were all still young and full of hope, and the future beckoned to us with its infinite possibilities.

- Latest

- Trending