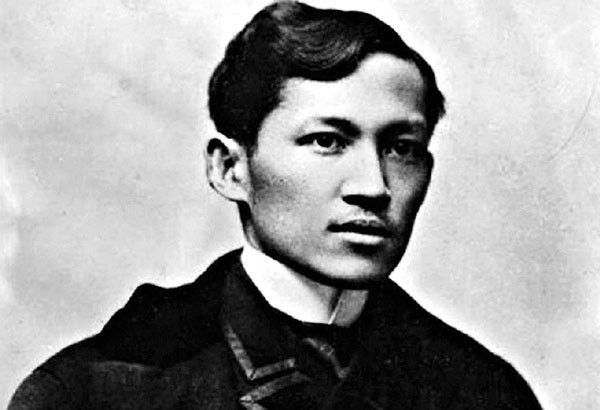

Jose Rizal’s ideals and ideas

Jose Rizal’s ideals were a product and composite of the teachings of what is known as the philosophy of Enlightenment. That stage of philosophy marked the dawn of the eighteenth century in Europe and continued to the 19th century.

Friar injustices and Spanish misrule. Jose Rizal’s writings transformed his stature from a writer and propagandist against social and religious injustices of Spanish rule in the Philippines that made him into a national hero.

He had far more writings of note and importance. But his two novels – Noli Me Tangere and El Filibusterismo – are his most prominent achievements. In these works, his main mouthpieces of change were fictional characters: Crisostomo Ibarra (as Ibarra in Noli; alias Simoun, in Fili), Elias, Father Tolentino, and Tacio (the philosopher).

All other characters (Sisa and her sons, Maria Clara, Father Damaso, Father Salvi, etc.) were exhibits of the cruelties of his times on the lives and fortunes of Filipinos.

Precociously gifted. As an intellectually precocious child, Jose Rizal went to study in the best schools of the country as he became a young man. These were religiously-run schools (Letran, Ateneo and University of Sto. Tomas). Rizal excelled in school in part because of his intellectual gifts but, possibly also much more, because of high motivation to excel and learn.

Highly intellectually gifted, he came from a well-to-do family that valued education. He was the only sibling (among 10) to go to Spain for studies. Thus, so much was sacrificed to get him to achieve.

The Spain of Rizal’s time. The second half of the 19th century – the time when Rizal lived (from 1861 to 1896) – saw Spain experience its continuing decline. A long war of succession in the kingdom after the Napoleonic era had weakened it. Spain was highly dominated by Church influence in government. In other parts of Europe, liberal ideas had led the path toward separating Church and State, though in different forms.

The Philippines remained by far Spain’s most durable colony along with Cuba and Puerto Rico, the lonely remnants of Spain’s once vast American empire. Perhaps because of more distant geography, the colonial policies with respect to the Philippines were harsher and more stringent.

Along with other Filipino expatriates of the time, Rizal would be vocal in making the case for the reform of Spain’s colonial policies. The ideas of Enlightenment had breezed through Europe the century before, but Spain remained largely less affected by these strong winds of thought.

Rizal’s work comes from the influences of the philosophy of Enlightenment. The political and social reforms that he espoused embodies general ideas of tolerance, more liberty and the need for civil government.

Foreign study and work. In 1882 at 21 years of age, Rizal traveled to Spain to take up medicine in the University of Madrid. He further obtained a degree in philosophy and letters after finishing his licentiate in medicine. Medicine was to steady his occupation. However, his heart and mind came to be more focused on the injustices inflicted by Spanish misrule over his country of birth.

His foreign sojourns would move him to different European countries pursuing his interests and his thirst for knowledge. He would live in England, in France, and in Germany. He would travel to other parts of Europe more transiently. Through apprenticeships and assistantships, he would learn the craft of medicine more. But through his curiosity, he would enrich his world-vision.

To accomplish these, he would rely more fully on family support. His heart was in his writing. In that mode, there was income-support to be earned.

His two novels were written and published in Europe. His Noli was written mainly in Spain but finished and published in Germany in 1887. His El Filibusterismo was written on his second trip to Europe and was printed in 1891 in Belgium.

The Enlightenment philosophers could be directly learned through readings of their work. But indirectly, they could be learned from public forums, saloon discussions, coffee shops, and masonic lodges. So there were many venues to learn from, indirectly.

Rizal was the party type, the debater in public discussions (a mainstay of the propaganda movement of Filipino exiles who tried to influence Spain’s colonial policies in Madrid), and a propagator of ideas of his own original thoughts. He was a serious library-museum researcher. He spent long days transcribing Morga’s Sucesos de las Islas Filipinas in the British Museum. There was no chance that he would have missed the encyclopedia, the fount of knowledge that writers of the Enlightenment enlarged.

“Ideas of the Enlightenment.” The advancement of individual liberty, social progress, tolerance, scientific knowledge, constitutional government, and separation of church and state: these were the main ideas of the Enlightenment. Together, they tended to undermine the authority of both monarchy and Church. They questioned the orthodoxy of fixed ideas.

The major philosophers of the early period included Descartes, Locke, Spinoza, Diderot, Hume, Kant, Rousseau, Adam Smith and Voltaire. The ideas of these philosophers were accessible through their writings. Did Rizal encounter them directly?

The biographies of Rizal have not focused on the details of his intellectual growth and the influences of his mentors and forebears. Though he massively picked learning from history, the classics and literature, there are few references concerning those writers who have directly influenced his thinking.

His letters as a young man were chatty and covered mundane affairs, not intellectual ones. His professional correspondence, for instance, with Dr. Ferdinand Blumentritt, were already at a high level of maturity and did not give hints of his intellectual heritage.

In his writings, he was sparse in revealing such heritage either. He has a great facility in absorbing and retelling contemporary events of his times. He was quick and direct and cutting in his political writings. And his arguments in his more thoughtful pieces tell us how he absorbed and learned from others.

An example of his immersion in other works however is provided in his “Reply to Barrantes’ criticism of the Noli Me Tangere” (Jose Rizal, Political and Historical Writings, vol. VII, National Heroes Commission, 1964, p. 191), who criticized the small circulation of the book early after its publication.

Rizal asked, rhetorically: “Find out also the number of copies sold of the works of Voltaire, Rousseau, Victor Hugo, Cantu, Sue, Dumas, Lamartine, Thiers, Aiguals de Izco, and others and by the consumption of numbers you have an idea of the number of consumers.”

Thus, I surmise he had read Voltaire and Rousseau but learned indirectly from others.

My email is: [email protected]. For archives of previous Crossroads essays, go to: https://www.philstar.com/authors/1336383/gerardo-p-sicat. Visit this site for more information, feedback and commentary: http://econ.upd.edu.ph/gpsicat/

- Latest

- Trending