Delicacies and confluences of betrayal

When a novel features two sisters in a triangle, the usual recourse is to portray one as the stronger character, while the other often necessarily emerges as the survivor.

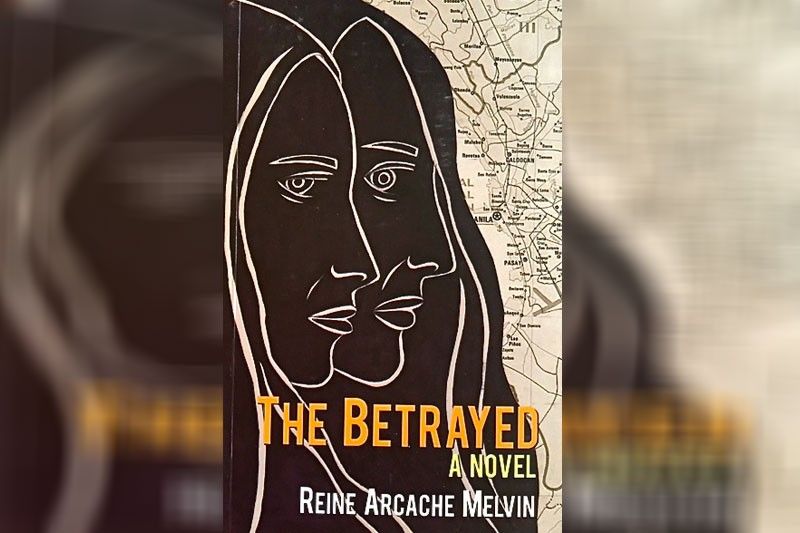

In her recently released first novel, The Betrayed, published by Ateneo de Manila Press, the consummate fictionist Reine Arcache Melvin adheres to this literary convention, but succeeds in stalling the reader from any judgment until the final pages.

She weaves a tantalizing narrative with such prose of exactitude, of grace-notes precision, with a delicacy that remains beholden to the story’s inexorability.

The rhythmic, steadily looping cadence of inevitability wraps around, within, and through the lives of the two sisters, Lali and Pilar, and the man they get to share, Arturo. So engagingly is this conducted on the strength of deft characterization, contrapuntal musings and reworked decisions — all subject to a proliferation of flashbacks and backstories.

Then too, the dense configurations often transcend the episodic ménage a trois, tweaking as they do the layers of realism that tell of our country’s birthright and inordinate fate.

Lali, Pilar and Arturo undergo detailed renderings of the environments that are virtual class divides between gardens that turn into jungles and forests that lead to clearings of epiphany.

The attendant characters are shamelessly familiar, if at times conflated without so much as an attempt at mocking our contemporary history.

The sisters’ father, Gregorio, finds himself in exile in San Francisco, fleeing with his family to save them all from the dictator who is simply called The General. Gregorio’s assassination abroad brings back his family, together with Arturo, the General’s godson who has decided to marry Lali. A people’s revolution casts out the dictator, whose eventual demise in Hawaii results in an embalmed corpse that his family aspires to have a hero’s burial back in Manila.

But Manila, as well as the rest of the islands, has just transferred political power to a new set of elites, led by President Peachy, who employs religiosity to explain away disasters. Her brother Ricky wields the actual power, as a composite of controversially dissolute presidents and a First Gentleman.

A shadow environment is composed of unyielding superstitions such as the garlic-wreath protection of pregnant women from an eclipse, plus an array of faith healers, fortune tellers, a Hong Kong real-estate broker who dabbles in Taoist magic, even a grandmother who’s been dead in the boondocks for three decades but whose body does not decompose, rather serve as a seekers’ haunt in exchange for donations.

Rival factions hold sway all over the countryside: hacienderos with the military and vigilante squads protecting their fiefdoms against Christian lay organizations led by religious sisters, who are accused of being Communist guerillas, with their party functions identified through the placement of moles in their faces. A beheading is conducted for the camera of a foreign journalist. Villages are burned by contending politicos. And a bunch of lepers is sent to disperse a political rally.

Through all these, the main characters undulate to the dance of love, lust, power, and passionate respect for the past whose ghosts pervade the present. The author imbues her protagonists, in this case Pilar, with a command of prescient language.

“… Because she couldn’t speak, she pressed her body against his. She imagined he was somebody else, a man she didn’t know. She wanted to feel desire, to go through to the end, like pain, like death, but everywhere she touched him she kept hitting the walls of her narrow, frightened self. She looked at his closed eyes and half-parted lips and thought of all the women who let themselves be sucked and touched and bitten by men they didn’t want. For the first time in her life, she was afraid she would become one of them.”

As aristocrats of an inchoate society’s matrix of emotions and expectations, they betray both custom and ceremony.

“Marilou had spent more than half of her life learning to attract men. Those skills were worthless now. Every society imposed a limit on a woman’s desirability. In Manila, the cut-off date came early. Lali reached for her mother-in-law’s hand and squeezed it lightly, sorry for her, and afraid for herself.”

And the strong-willed Lali speaks of her husband:

“… He had been young and not cynical. A smooth-skinned boy who smelled of cognac and after-shave. The money in his smile, the symmetry in his features. Generations of carefully chosen wives and husbands had led to this—a pretty boy with exquisite manners, perfect teeth, and a disconcerting blend of entitlement, sensuality, and kindness.”

Arturo himself recollects:

“Nothing had changed in this country, Lali had told him. Not in the past hundred years, not in the hundred to come. Nothing except the increasing weakness of men like himself. The sons of sons, weaker and more sentimental and more spoiled, with each generation. Only the women they married kept the family strong.”

Another recollection is of a pithy quote from a legendary coup leader who would become a senator:

“The greatest threat to this country, Jimbo had said, is a leader with education, integrity, and no social status.”

When Arturo revisits the presidential palace from where his godfather had ruled, he sees a family portrait that still hangs in its walls:

“Only the First Lady remained interesting. The artist’s brush softened but couldn’t disguise the set of her mouth, that peculiar blend of naiveté and ruthlessness in her eyes. She and her husband had stolen and bullied and perhaps killed, but their extravagance continued to fascinate the country. They had been kind to him.”

Kindness, violence, inadvertent betrayals all jockey for pole position against love’s very own hesitations. The family stays premier, even if the qualities of soap opera are abandoned by the ruling class. This novel has an archipelago of contradictions down pat, yet pulsing.

In a back cover blurb, Jessica Zafra pitches for Melvin’s accomplishment:

“Her beautiful, sensual, visceral writing shows us that the past is not really a foreign country, but our own country in an eternal loop. As one of my favorite movies says, ‘We may be through with the past, but the past is not through with us yet.’ And speaking of movies, this novel is ready for the screen.”