Specters of comparison, ghosts of disunited colors

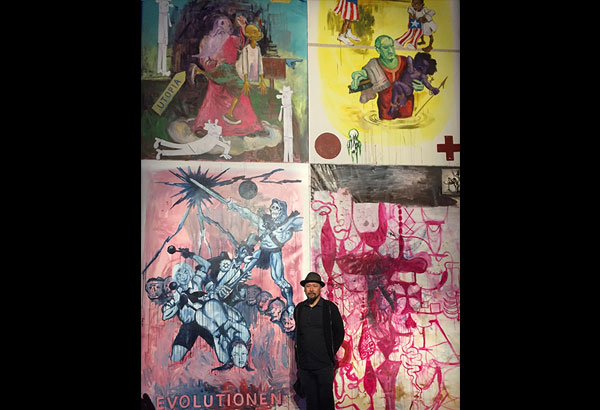

Manuel Ocampo with his “Torta Imperiales” suite of paintings

The Philippine Pavilion opens at the 2017 Venice Biennale

It is bound to get heady, dear readers.

You could swear you have recruited yourself in a Gabriel Garcia-Marquez novella: inside the house it is raining, while outside remains bone-dry. But this is not a magic-realist, Latin American literary incantation. The installation is by Vajiko Chachkhiani, and centers on a house from a Georgian countryside titled “Living Dog Among Dead Lions.” Lizard people, aliens and tentacles star in a suite of carved drawings that evoke Japan-by-way-of-America “Saturday Fun Machine” animation. But the artist, Mi?elis Fišers, is actually — get this — Latvian. Another pavilion features a science-fiction-like “Jesus Factory” churning out edition after edition of disintegrating and corrupting imitations of Christ. Some Spanish inquiry about the nature of religious as well as artistic representation, perhaps? Wrong. This awe-inspiring installation by Roberto Cuoghi is at the Italian Pavilion of the 57th International Exhibition of La Biennale do Venezia or the Venice Biennale. It speaks about magic, rituals, transformation and the supreme power of the artist.

Going from station to station in this year’s edition of the biennale with its theme “Viva Arte Viva” shows how contemporary art practices have broken down walls (even if walls are making a comeback in world politics): the art oeuvres are rooted in the specific countries of origin, but they have become transcendent, with concerns spoken in the universal, something that found a way out of the mirror, utterly border-less.

Take the case of our own entry into the world’s biggest contemporary art event: “The Spectre of Comparison” featuring the artworks of Manuel Ocampo (“Torta Imperiales” paintings) and Lani Maestro (installations of blue neon, ruby-red neon, as well as wooden benches) as curated by Joselina “Yeyey” Cruz.

“If there is such a thing, I think I belong to the country of making art,” says Lani Maestro. She left for Canada at the height of the Marcos dictatorship, while Ocampo went to the States during the ’80s.

Maestro continues, “It’s interesting, this whole notion of exile. It talks about belonging, so for a long time it was like two separate things: ‘to be’ and ‘to long.’ It is an important state of mind to be longing for a place that we don’t have.’”

Manuel says he has also felt this un-belonging and it is important in his opus with its chaos of images and multiplicity of references. It is actually bannered in one of his paintings: “To masturbate is to make your homeland.”

“My paintings talk about identity,” he shares, “but at the same time, make fun of it.” This is a view that is complex, layered, and always in flux. “You know, every time I become legalized in a country (America, Spain), I move away (laughs). I’m not standing on fixed ground most of the time.”

Lani explains, “I think it’s important, this idea of being outsiders. This feeling of ‘otherness’ is an interesting condition. And once I’ve realized that, I knew that I can be free wherever I am in the world. And in the end, nations are just names, categories.”

Manuel agrees. He says they are “social constructs.”

The experiences of these two Filipino artists who have made quite a name for themselves in other countries draw a parallel with what our wandering hero Jose Rizal had gone through.

The exhibition’s takeoff point is how Rizal (using his Noli Me Tangere protagonist Crisostomo Ibarra as his avatar) demarcated his homeland side by side with the European Other, something that enfleshed the “double-consciousness of a colonial emigre of the 19th century.”

Curator Yeyey Cruz writes, “The gaze of the specter has been accorded to (Maestro and Ocampo), not only as artists knowledgeable of several worlds — having lived in and inhabited them — but as artists whose art-making produces a global (vision), interrupted by discursive and complex imaginings that allow for the consciousness of worlds constructed across geographies, temporalities and the haunting of specters.” She says that the push-and-pull between Lani’s and Manuel’s art is very strong.

“For me,” explains Lani, “it’s not about me being here (as an artist at the Venice Biennale), but about being here in conversation with others.”

Multiple dialogues on a much bigger stage, we should say. The Philippine pavilion has moved from the 18th century Palazzo Mora (the venue of our 2015 pavilion) to the Arsenale, one of the main exhibition spaces of the Venice Biennale. Senator Loren Legarda — the visionary and principal advocate of the Philippines’ participation in the Venice Biennale — says, “Now that we are in the main hall, the challenge is to constantly outdo ourselves.”

“Without the tenacity of Senator Legarda, all this would not have happened,” notes NCCA chairman Virgilio Almario, who also takes on the role of commissioner for the Philippine pavilion. (The chairman is also preoccupied with translating canonical works into Filipino. In the bag is Plato’s The Republic; in the works is a book by Aristotle.)

Senator Legarda hopes that more Filipinos will continue to participate in the global art conversations.

We live in interesting times, as evidenced by the works in the 2017 Venice Biennale. Walls are rising, falling down, rising up again. And yet despite the thrum of sirens, clashes by the borders, and the riot of disputes, conversations in art is still possible. So is magic.

* * *

The Philippine Pavilion — a project of the National Commission for Culture and the Arts (NCCA), the Department of Foreign Affairs (DFA), and the Office of Senator Loren Legarda, and with the support of the Department of Tourism (DOT) — had its vernissage last May 11 and is open to the public until Nov. 26.